June 2023 Executive Summary for the Eighth Report of the Federal Monitor, Covering the Period from October 2022 through March 2023

Federal Monitor

Case 3:12-cv-02039-FAB Document 2430-2 Filed 06/13/23

This is the eighth Chief Monitor’s Report (CMR-8) outlining the compliance levels of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in relation to the Consent Decree entered between the United States and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. This report provides the eighth assessment following the four-year capacity building period established by the Consent Decree that ran from June 2014 to October 2018 and covers the period from October 2022 through March 2023.

During the CMR-8 reporting period, the Commonwealth’s achievements towards partial and/or substantial compliance with many of the paragraphs remained largely the same with minimal progress. Further, while improvements to use of force (UOF) reporting and tracking have been made, the conduct of training on the requirements of the paragraphs assessed has continued to regress. Repeated issues like poor documentation of probable cause and the use of boilerplate language on arrest reports, failures in supervision to issue corrective actions, and exceeding timelines in Force Investigation Unit (FIU) investigations and Commissioner’s Force Review Board (CFRB) evaluations of UOFs, are examples of items raised in previous CMRs and noted again in this report. Adding to these issues are continued concerns over the lack of resources and staffing in several PRPB divisions and units, like the Auxiliary Superintendency for Education and Training (SAEA) and the Auxiliary Superintendency for Professional Responsibility (SARP), which further hamper the Bureau’s ability to move compliance forward.

The Reform Unit also experienced leadership changes during the CMR-8 reporting period. However, minimal disruptions to the Unit’s ability to produce data and documentation and facilitate the Monitor’s Office’s site visits were experienced. The work done by the Commonwealth’s contractor, AHDatalytics, via the dashboards and ReformStat will be key to assisting the new leadership. Further, the Bureau must acknowledge that it, not the Monitor’s Office, is ultimately responsible for demonstrating compliance with each area of the Agreement. This requires improvements to the Bureau’s ability to audit and monitor itself – rather than relying on the Monitor’s Office’s CMRs. It is the hope of the Monitor’s Office that the future implementation of various management processes, like ReformStat, will assist the Puerto Rico Police Bureau (PRPB) in working towards this goal.

Despite these challenges and continued stalled progress in compliance with many of the paragraphs, the Monitor’s Office is encouraged by the Commonwealth’s and PRPB’s progress in a number of areas, including, improvements to the accuracy in UOF tracking and reporting, the promotion of over 500 sergeants, progress on the IT Needs Assessment and Corrective Action Plan (CAP), finalizing the Training Plan, and the Bureau’s openness to collaborate in drafting similar implementation plans for Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Investigations and Arrests and Searches and Seizures.

Development of these plans will be key to ensuring that the Commonwealth allocates the necessary resources and maintains the proper management to address the issues continuously raised by the Monitor’s Office. The provision of the necessary resources, equipment, software, and staffing will be key to the Bureau’s ability to carry out the implementation of the above noted plans.

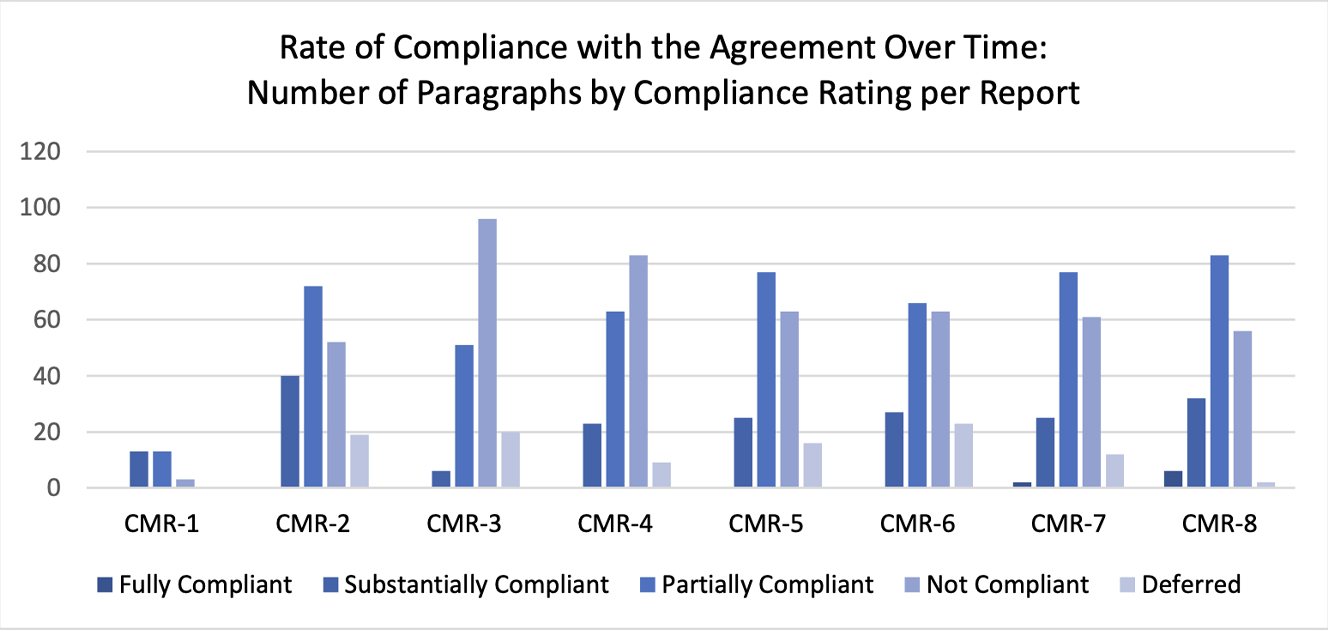

Further, when examining the total paragraphs assessed in this report (N=179) in comparison to the previous report in which these sections and paragraphs were assessed (CMR-6; N=179), the Monitor’s Office notes that PRPB has achieved some progress during this reporting period. For example, 83 paragraphs met partial compliance and 56 paragraphs were rated not compliant during this reporting period, in comparison to 77 paragraphs rated as partially compliant and 61 as not complaint in CMR-6. Further, when reviewed comprehensively, almost 68% (N=121) of the paragraphs meet either partial, substantial, or full compliance in CMR-8 in comparison to 52% (N=93) in CMR-6.

Monitoring Activities During CMR-8

Over the past six months the Monitor’s Office conducted six site visits to PRPB headquarters as well as various regions of the island including Aibonito, Utuado, Fajardo, Caguas, and Carolina. These field visits provided an opportunity for the Monitor’s Office to hear directly from supervisors and officers on the front line, speak with members of the Commonwealth community, observe operations, receive system demonstrations, and validate the assessments they made as part of their review of over four thousand policies, documents, certifications, audio recordings, and case files and reports provided for review during the CMR-8 reporting period. The Monitor’s Office also reviewed 80 policies, forms (PPRs), and protocols under paragraph 229 of the Agreement, observed various PRPB community engagement efforts, participated in 8 system demonstrations, and were present at several demonstrations and protests during the reporting period.

In addition, during the CMR-8 reporting period, the Monitor’s Office participated in one status conference in January 2023. It focused on updates related to CMR-7, sergeant promotions, Training Plan, IT CAP, the Supervision and Staffing Plan, the Equitable Sharing Program, and integrity audits. An IT Needs Assessment was filed with the court, and the Bureau and the Parties began working on the development of the IT CAP. Further, 90-day status updates to the Staffing and Promotion Plan and the final Training Plan were submitted to the court by the Commonwealth during this reporting period.

During this reporting period, the Monitor’s Office also conducted a community listening session. This meeting was attended by over 30 representatives from various organizations representing people with disabilities and provided the Monitor’s Office with an opportunity to hear directly from the community about their concerns and interactions with PRPB.

Looking Forward to CMR-9

The Monitor’s Office stresses to the Commonwealth that it must address the issues repeatedly raised in its prior CMRs. Improvements to compliance rest on the Commonwealth’s ability to systematically and intentionally address the concerns raised in the CMRs.

While the Monitor’s Office acknowledges that improvements to compliance in some of the paragraphs require extensive changes to PRPB’s processes and significant fiscal investments, like the acquisition of a new records management system, other paragraphs require less extensive improvements. In most cases, revisions to policy, delivery of training (virtual, in-person, and roll call), increased accountability, or improved reporting and documentation would suffice and demonstrate improved compliance. The pathways forward noted within the CMRs outline the necessary steps the Commonwealth must take to address compliance.

Further, it is the Monitor’s Office’s hope that future improvements to the structure and organization of the Reform Unit will allow for the Bureau to improve its ability to set an overarching strategy and plan to achieve compliance with all areas of the Agreement and self-monitor.

The Monitor’s Office will continue to review documents produced by PRPB and the Commonwealth in demonstration of compliance, conduct additional field visits, observe related training sessions, observe PRPB’s community engagement efforts, and conduct interviews with both PRPB personnel and community stakeholders. Further, during the CMR-9 reporting period, the Monitor’s Office hopes to continue to conduct additional community listening sessions to share the reform status and hear directly from the broader Puerto Rican Community.

Summary of Compliance by Section

The following summary provides an overview of the Monitor’s Office’s compliance assessment for each area of the Agreement.

1. Use of Force

In all previous CMRs the Commonwealth’s progress towards achieving compliance with UOF has been hampered by its inability to validate its UOF numbers. This issue has been repeatedly raised as compliance assessments of several of the paragraphs within this section of the Agreement require a comprehensive review of UOFs. The Commonwealth and PRPB, working with USDOJ and the Monitor’s Office, developed a Provisional UOF Plan to address the inconsistencies in its UOF tracking. PRPB formally implemented the Provisional UOF Plan in July 2022. The Provision UOF Plan increased supervisory layers of review to identify and correct errors and/or discrepancies in the UOF reporting forms within PRPB’s GTE system. The Monitor’s Office and USDOJ approved the interim plan. PRPB was reminded that a more comprehensive, less labor intensive system/plan needs to be developed.

As it relates to improving UOF reporting, during this reporting period, PRPB was able to demonstrate that it could provide accurate UOF numbers. What also aided PRPB in accomplishing this task was its contractor, AHDatalytics, which developed a UOF dashboard that helped identify discrepancies in UOF reporting within the GTE system. This assistance provides the Reform Unit with the ability to comprehensively review whether certain procedural or documentary steps were taken as part of the force reporting process in the field.

During this reporting period, PRPB reported 802 UOFs in 439 incidents. A cross check of various units’ data by the Monitor’s Office determined the accuracy of the data and that the information from PRPB’s GTE system is comprehensive. It should be noted that the Monitor’s Office, in reviewing whether PRPB officers are preparing and submitting UOF reports (PPR 605.1) in the timeframe as outlined in Bureau policy, has determined that PRPB has made significant progress. In the 76 UOF reports reviewed 73 (96%) were prepared and submitted in the timeframe outlined in policy. In the remaining three incidents PRPB produced documentation showing that the reports were late - two were one day late and one was two days late. These are significant improvements that have resulted in improved compliance ratings. However, the Provisional UOF Plan is an interim plan while the Bureau develops a system that identifies discrepancies in real time and does not have to rely on various levels of review for identifying errors in the system and making the required corrections.

Consistencies in the UOF data largely affect many of the paragraphs in this section. Other topics such as the Force Investigation Unit (FIU), Force Review Boards (FRBs), Crisis Intervention Training (CIT), SWAT, and crowd control procedures also impact PRPB’s overall compliance with this section. As it relates to FIU, the Monitor’s Office continues to remain concerned regarding the length of time FIU is taking to complete its investigations. However, there was some improvement in the timeline as the Monitor’s Office observed more cases completed within policy (18%), but in most cases reviewed the investigations were not completed within the 45-day requirement. Changes to FIU personnel (a newly designated commanding officer) which occurred in the latter part of the reporting period and PRPB’s commitment to add much needed investigators as recommended by the Monitor’s Office in previous CMRs is encouraging. Similarly, in the Monitor’s Office’s review of Commissioner Force Review Board (CFRB) evaluations, while the evaluations were objective, they also were not timely. CIT, like UOF, has also been an area of discussion and focus for the Court in the past few months. Despite the completion of PRPB’s CIT pilot program in November 2020, the Bureau has lagged in its efforts to complete an evaluation of the pilot and expand the program to other areas of the island. Due to these issues in January 2022, the Court requested that PRPB work with USDOJ and the Monitor’s Office to establish an evaluation committee and move progress forward with expanding the program to other area commands. While PRPB has made some progress in these efforts, by producing a draft evaluation and interviewing potential CIT coordinators, its progress continues to lag due to recruitment and training challenges. At the end of the reporting period, PRPB noted that training of additional CIT officers was scheduled for May 2023.

Notwithstanding the issues noted above, the Commonwealth has demonstrated progress in many of the UOF paragraphs. Much of the efforts made in this reporting period can be attributed to PRPB’s continued collaboration with AHDatalytics, the Commonwealth’s contractor, who has helped PRPB develop several UOF related dashboards, which include “Compliance with Reports”, “Use of Force Statistics", “Requests from the Monitoring Team”, and “Specialized Tactical Unit Mobilizations.” These dashboards are useful to the Monitor’s Office as they serve as another tool in assessing PRPB’s compliance with the Agreement. The positive efforts made in this reporting period will, if continued, prove beneficial in subsequent reporting periods.

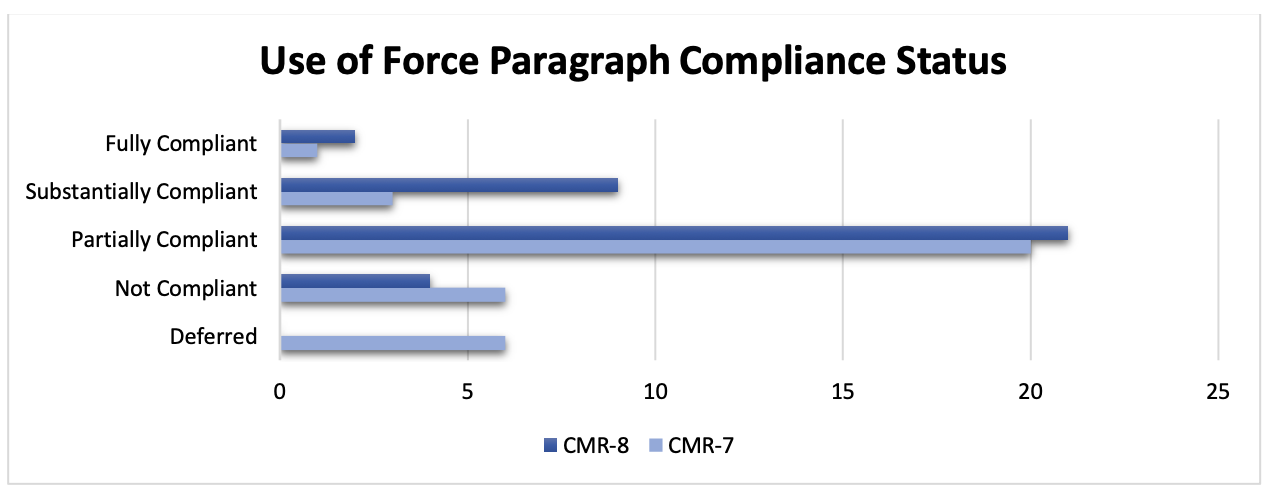

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the 36 paragraphs assessed during this reporting period within UOF reflects improvement in levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-7, 56% of paragraphs (20 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant and 8% (3 paragraphs) were assessed as substantially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 58% of paragraphs (21 paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant and 25% (9 paragraphs) were found to be substantially compliant (paragraph 33 moved to fully compliant). See figure 2.

2. Searches and Seizures

Poorly written and incomplete filing of arrest reports continue to be a serious issue in PRPB despite several assessments from the Monitor’s Office raising this issue. Many officers are still not properly documenting the particular facts in each arrest case, which has led, in many cases, to officers insistently using boilerplate, conclusive, and repetitive language in their reports. Officers constantly fail to include all the required forms in arrest files, and supervisors and commanders are failing to catch these deficiencies and take corrective action. Some arrest files, inconceivably, were submitted to the Monitor’s Office without a police report. All these unaddressed issues have left the Monitor’s Office with no other choice but to rate PRPB’s performance in this area as not compliant. The Monitor’s Office can confidently state that if PRPB officers, especially supervisors and commanders, were to do due diligence when completing arrest and search reports, the compliance rates would be significantly higher. Accountability for those failing to follow policy and properly document arrests is also necessary to move compliance forward.

When it comes to investigative stops and detentions, PRPB is not performing any better in this category. The Highway Patrol Division (HPD) submitted 13 randomly selected detention/stops files for review, and it failed to comply with policy requirements in more than half of the files, leaving the reader without a clear understanding on whether the police had more than reasonable suspicion when officers detained and/or arrested the subjects. Seized Property/Evidence forms are not completed or included with every arrest file. Some Property and Evidence rooms are not properly secured - lack of ventilation in some cases and size in some others.

The assessment of search files has always fared better, and this reporting period is no exception. Search warrant applications are being properly reviewed and approved by supervisors, and the resulting arrests are likewise being reviewed and evaluated by supervisors and commanders. Even when conducting consent searches, PRPB has shown progress compared to the last CMR. During the previous reporting period, the consent search form was missing from most files; this reporting period, all the consent search cases reviewed contained properly completed consent forms.

Finally, near the end of this reporting period, the Commonwealth, along with USDOJ and the Monitor’s Office, began working on an Implementation Plan to address many of the issues raised in the Monitor’s previous CMRs. The Monitor’s Office looks forward to working with the Commonwealth and USDOJ to finalize this plan during the CMR-9 reporting period.

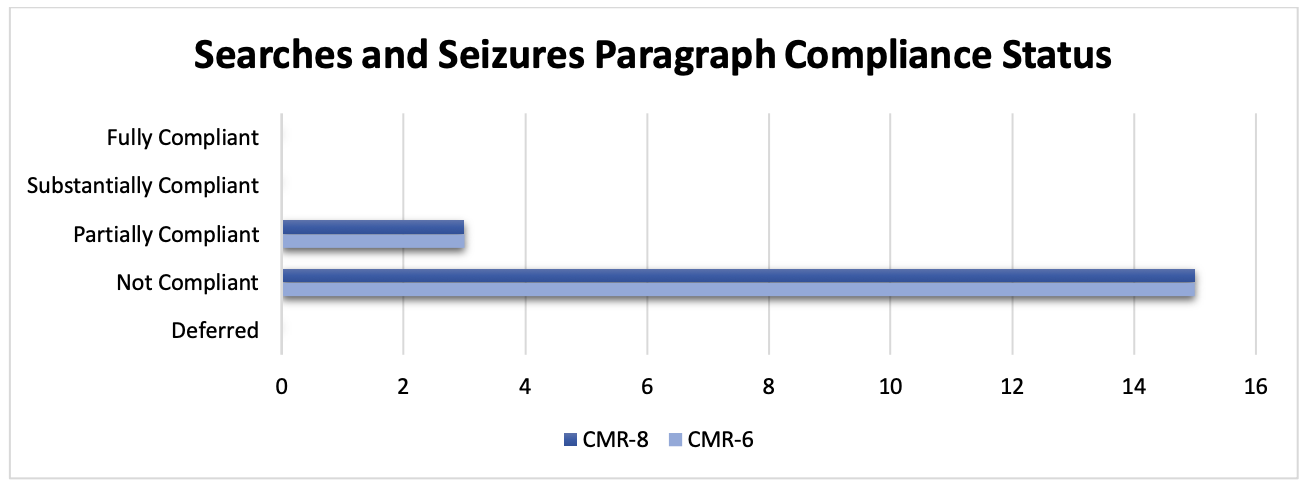

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the 18 paragraphs assessed during this reporting period within Searches and Seizures reflect the same levels of compliance to what was noted in previous CMRs. In CMR-6, 83% of paragraphs (15 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where the same number of paragraphs were found to be partially compliant. See figure 3.

3. Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination

The review of the documents and data provided to the Monitor’s Office during this reporting period continued to demonstrate issues raised by the Monitor’s Office in previous CMRs. As noted in previous CMRs, much of PRPB’s progress in this area remains at partial or non-compliance. Of the 21 paragraphs within Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination, a limited number are assessed every six months. A comprehensive review of this entire section was provided in CMR-7 and will be provided again in CMR- 9. For CMR-8, only 10 paragraphs (paragraphs 84 - 86, 88 - 90, 92 - 93, 96, and 99) are assessed in this report and, in most instances, only specific targets within these paragraphs are assessed biannually. The compliance targets assessed in this reporting period are bolded in the paragraphs identified above. The paragraph compliance targets assessed in this reporting period primarily focus on PRPB’s efforts to demonstrate implementation of training and processes related to hiring, the civilian complaint system, performance evaluations, juvenile case management reporting, hate crime reporting, and bias-free policing training. There are no significant changes in PRPB’s progress in meeting the compliance targets assessed in this reporting period as compared to CMR-7.

A review of 54 SAIC and SARP investigations involving PRPB members was conducted during this reporting period, per paragraph 99. All 54 cases were domestic violence (Ley 54 violations). No sexual assault cases involving PRPB members were submitted for review. Therefore, with no review of sexual assault investigations, the Monitor’s Office is not able to assess whether PRPB documents the use of a trauma informed response method, consistently provide victims with available resources on support or safety, or follow-up in a timely manner with the victim, as required by paragraph 93. The Monitor’s Office notes that changes to the manner that police reports are written, use of an investigative checklist, supervisor accountability, and increased training, as recommended in previous CMRs, will improve the Commonwealth’s compliance with related paragraphs.

Several high-profile events and incidents occurred during this reporting period that have renewed the focus on domestic violence and sexual assault cases, particularly those involving PRPB members. The Monitor’s Office reviewed 54 domestic violence SAIC and SARP investigation files and found that PRPB does follow its policy related to seizing officer weapons and referring the employee to the employee assistance program (EAP) when a PRPB member is involved. Findings made in CMR-7 stressed the importance of PRPB being consistent with policy in how it investigates cases involving PRPB members. PRPB should also consider how it assists its officers with dealing with the stressors of the job. The Monitor’s Office emphasizes that cases must be accurately investigated and processed in a timely manner to provide transparency and accountability. The Monitor’s Office also recommends that the Commonwealth develop a comprehensive response plan addressing the manner in how it deals with cases involving PRPB members.

On March 6, 2023, the Parties met to discuss the development of an implementation plan focused on PRPB compliance with the sexual assault and domestic violence provisions of the Agreement, specifically paragraphs 93 to 99, 80 to 82, and 84 to 86 (as they pertain to the administrative investigations of sexual assault or domestic violence allegations involving PRPB personnel). The objective of the Plan is to address many of the issues noted by the Monitor’s Office and improve compliance. Issues such as training, the quality of the investigation files, victim centered practices, supervision, internal investigation practices, as well as other issues related to staffing and resources will be addressed in this Plan. An initial outline of the draft implementation plan was provided to the Parties in March 2023. The Monitor’s Office expects to review further drafts of the implementation plan in the early part of CMR-9.

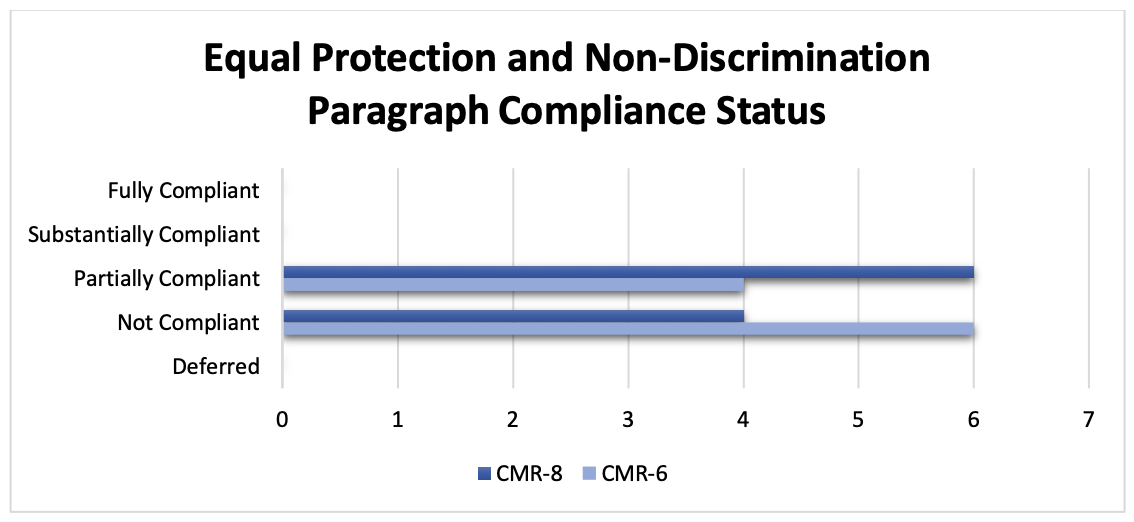

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the 10 Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination paragraphs reflects marginal progress in levels of compliance to what was noted in previous CMRs. In CMR-6 40% (4 paragraphs) of the 10 paragraphs assessed were partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 60% of the 10 paragraphs (6 paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant. See figure 4.

4. Recruitment, Selection, and Hiring

The most recent Paragraph 13 Committee Meeting presentation showed that 200 recruits will be added to the ranks of PRPB by July 2023. Police recruitment, selection, and retention are critical to the advancement of community policing and of the policing profession in general. However, recruitment and staffing shortfalls continue to plague law enforcement agencies across the United States. Nevertheless, PRPB provided data that demonstrates a concerted effort both to recruit qualified candidates, and to vet them thoroughly.

Overall, PRPB has put a tremendous effort into addressing these challenges with a comprehensive recruitment plan and effective recruitment programs that solicit recruits from a broad cross-section of the Puerto Rican community. However, gaps remain in the training of recruitment officers and the implementation of the recruitment plan in practice. The recruitment plan includes several strategies to attract diverse applicants.

During the reporting period, the Monitor’s Office reviewed proposed updates to PRPB’s Law 65 recruitment policy (GO 501 - Recruitment) and the 2022/2023 Recruitment Strategic Plan and gave feedback to PRPB). The Monitor’s Office has also interviewed members of the Recruitment Division, HR Division, PRPB members, the Academy, and Paragraph 13 Implementation Plan committee members, and reviewed all pertinent forms and recruiting materials that are being used by the Bureau. It should be noted that as of March 31, 2023, the new recruitment regulations, and the general order of the Recruitment Office, which includes the implementation of Law 65, are on hold until further thought and planning on establishing a cadet program. Under Paragraph 13, a sustainability plan has been submitted to the Court. It is hoped by the Monitor’s Office that a new Police Academy class (235) will be operational by CMR-9, to help fill the void of many retirements.

The Monitor’s Office finds that PRPB is partially compliant with the Agreement regarding recruitment, selection, and hiring policies and procedures. PRPB has tried to recruit and hire qualified personnel and develop recruitment strategies that promote inclusive selection practices that better reflect a diverse cross-section of the Puerto Rican community. PRPB still needs to improve in certain areas, such as the development of training, continue to use CIT officers, as well as institutionalize many of these practices to achieve substantial compliance.

It should be noted that the Recruitment Division currently uses an INTERBORO platform that expedites the complete recruitment process. The Recruitment Division should also ensure that each recruitment officer in all areas in Puerto Rico be trained in recruitment and the use of the INTERBORO platform. The INTERBORO system makes PRPB more effective and efficient in recruitment and helps automate valuable information and statistics.

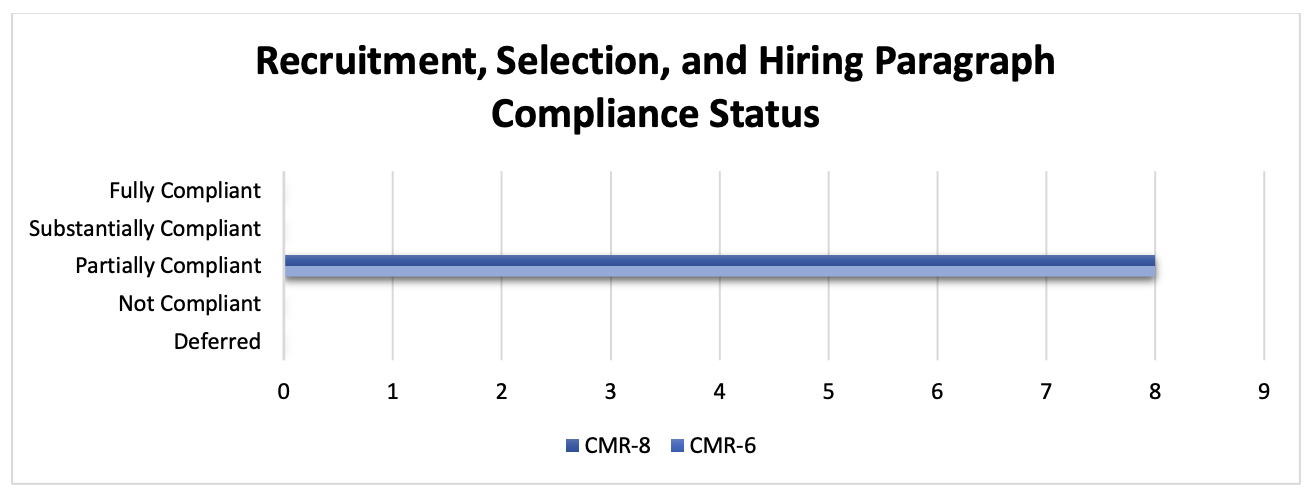

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the eight Recruitment, Selection, and Hiring paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect the same levels of compliance as what was noted in previous CMRs. In CMR-2, CMR-4, CMR-6, and CMR-8 all paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant. See figure 5.

5. Training

Police officer training is a fundamental developmental process that contributions to successful officer careers. While PRPB remains aware of the significance of this process, training continues to not be a priority. Specifically, PRPB did not achieve the mandatory 40-hour in-service training requirement that each officer is required to receive, per paragraph 129, during this training cycle.

The Training section of the Agreement is assessed annually and, in this report, covers the review period of April 2022 through March 2023. The Monitor’s Office’s assessment of PRPB’s compliance with training is based on the training documents submitted by PRPB, interviews with staff assigned to the Academy, Field Training Officers (FTOs), FTO Coordinators, and others involved in the development and conduct of Academy, in-service, and FTO training. Over the last year, PRPB has had to adjust its training delivery due to the larger than usual pre-service academy - Class #233 had over 400 cadets. The development and delivery of the new sergeants’ course to over 500 individuals also contributed to this adjustment. The shortage of training instructors to teach the pre-service and in-service training courses further hindered the Academy’s ability to operate functionally. As noted in previous CMRs, the staffing shortages coupled with the Academy’s inability to accurately document its training capabilities using the Police Training Management System (PTMS) must be addressed.

Much work remains for PRPB to achieve preliminary compliance with several of the paragraphs within this section. Specifically, the sections of in-service training, training record management, and curriculum development still need work to attain compliance. Within those areas, the provision of additional equipment to support training instructors in the delivery of scenario-based training and full use of PTMS to register, record, and evaluate training courses provided by PRPB needs improvement.

Although the Monitor’s Office was able to meet with and interview various staff involved in the development and supervision of training, PRPB failed to submit the data and documentation necessary for the Monitor’s Office to assess this area in a comprehensive manner. Documentation such as projected training calendars/schedules and course curriculum files were not provided. Additionally, despite the Monitor’s Office’s several requests for training calendars and schedules, none were provided in advance of the conduct of these trainings, and the Monitor’s Office was limited to observing one pre-service class during this CMR reporting period. During this reporting period the Monitor’s Office did receive and review supporting documents and related materials for the development of a comprehensive training program to supplement the 40-hour formal in-service training that is delivered at the beginning of shifts or tours of duty for all officers. These meetings are referred to as roll call training meetings.

Despite the challenges and issues noted above, PRPB continues to demonstrate its growth in the development and delivery of its FTO program. The FTO training program is modeled after national best practices and PRPB has demonstrated progress in the development, delivery, and practice of all aspects of this training program. PRPB must still find the resources for compensation or incentives for its FTO trainers. The FTO Program expanded its coverage of the island during this reporting period. The FTO Program is now in five districts: Bayamon, Caguas, Carolina, Fajardo, and San Juan. PRPB is commended on the progression of the FTO Program. It demonstrates PRPB’s commitment to the development of a new agent’s successful career.

In response to the Court, PRPB, in collaboration with the Parties, developed a Training Sustainability Plan. 1 Although the plan outlines PRPB’s projected efforts to address the issues the Monitor’s Office has noted in this and previous CMRs, much of these actions will not be taken and/or fully implemented until the end of 2024. The Monitor’s Office continues to stress that it is imperative that PRPB address its current training efforts to advance its progress towards compliance.

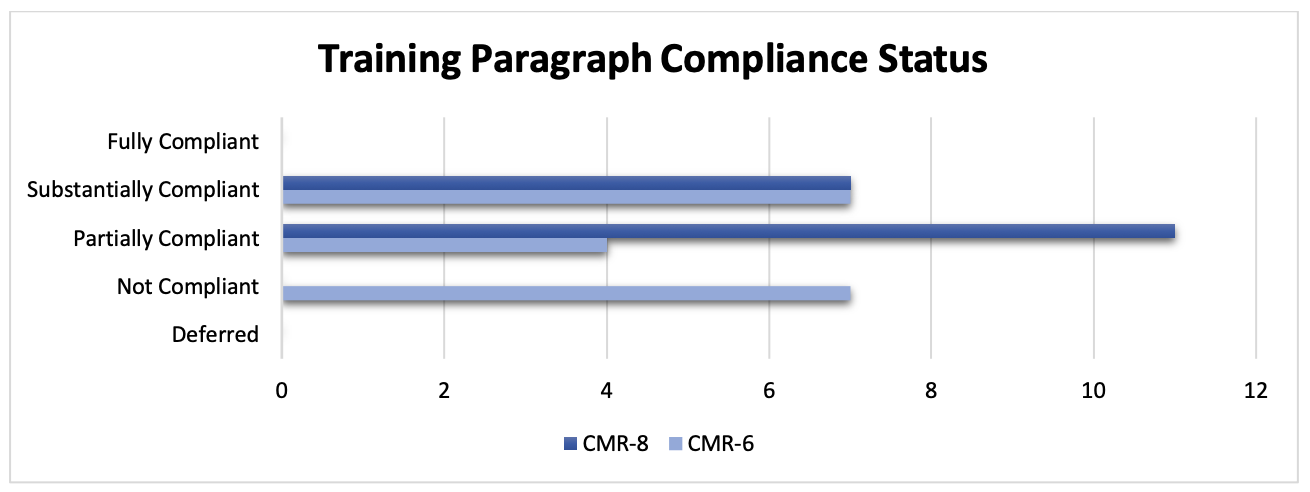

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 18 Training paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflects substantial improvement in levels of compliance compared to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-6 39%of paragraphs (7 paragraphs) were assessed as not compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 100% of paragraphs (18 paragraphs) were found to be partially or substantially compliant. See figure 6.

6. Supervision and Management

During this reporting period, the Commonwealth continued to struggle with achieving compliance with the Agreement due to the quantity and quality of its first-line supervisors, inconsistent supervision, poor management of promotional processes, failure to develop and institutionalize adequate information technology systems to support supervision (i.e., Early Intervention System (EIS)), and developing an effective comprehensive performance evaluation system. During the latter part of the reporting period, PRPB was able to develop a first-line supervisors promotion test. The Monitor’s Office was involved with all components of test development and approval. The test was administered in December 2022 to 1,414 members of PRPB. During grading it was determined that six questions needed adjustment, which resulted in 562 officers becoming eligible candidates for promotion. In February 2023, 533 officers were promoted to sergeants. It was also reported that all 533 new sergeants received the 40-hour required training at the Academy. After the promotion of sergeants, PRPB made substantial progress in moving compliance forward that will begin to be realized in CMR-9. In addition, in the February 2023 Staffing Plan, PRPB submitted a redistribution of personnel that should take effect during the 2022 – 2023 fiscal year. The Staffing Plan notes the Commonwealth’s efforts to comply with the related court order to implement the Staffing Plan and initial work on the development of the Integrity Unit policies and procedures.

As part of the Staffing Plan described in paragraph 13, PRPB identified that 740 supervisors for 110 precincts were needed based on a ratio of 6 first-line supervisors and a relief per unit. During CMR-7, PRPB reported that 103 officers were promoted to sergeants and an additional 533 were promoted to

sergeants in CMR-8, for a total of 636, leaving a shortage of 104 supervisors. Furthermore, in this Staffing Plan, the Commonwealth identified the need for 68 positions within the ranks of inspectors and colonels. PRPB submitted that during this reporting period, interviews, evaluations, and identifications of qualified officers took place. PRPB reports that a promotion ceremony will take place in May 2023 to promote the identified 68 high ranking positions.

During this reporting period, the Commonwealth named a board responsible for designing a promotion system, which included the administration of examinations and other more objective measures, complying with their goal. However, as reported in the past, officers interviewed continue to note issues with PRPB’s transfer policy, GO 305 (Rank System Transfer Transactions).

Further, the Monitor’s Office found that no new efforts have been made regarding EIS. Regarding Inspections and Audits, only four audits were completed during this reporting period. Although an Annual Report was produced and reviewed, the Monitor’s Office notes concerns over the lengthy timelines to complete and certify these inspections. No additional work has been conducted on Integrity Audits as the Commonwealth is working with the OSM to draft related policies and protocols.

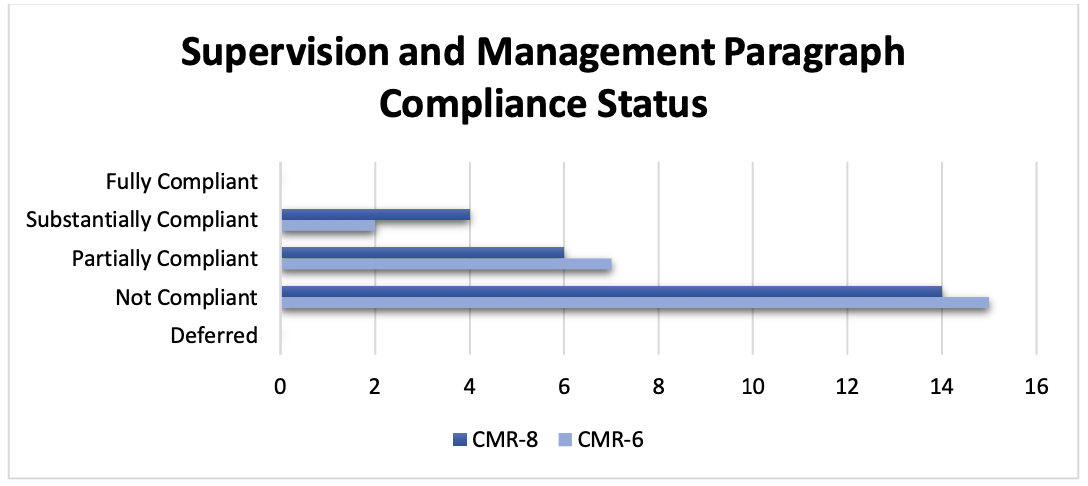

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the 24 Supervision and Management paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect slightly improved levels of compliance to what was noted in previous CMRs. In CMR-6, 29% of the 24 paragraphs (7 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant and 8% of the 24 paragraphs (2 paragraphs) were assessed as substantially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 25% of the 24 paragraphs (6 paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant and 17% of the 24 paragraphs (4 paragraphs) were assessed as substantially compliant. See figure 7.

7. Civilian Complaints, Internal Investigations, and Discipline

The Monitor’s Office now fully employs a bifurcated analysis of SARP investigation files into Phase I and Phase II. Phase I is the Monitor’s Office’s contemporary assessment of PRPB’s compliance with respect to the internal investigation of PRPB members. Phase II is the Monitor’s Office’s assessment of the adjudication phase of the case, which follows most investigations where a sustained finding has been entered. Phase I shows limited improvement. Phase II reviews of SARP case adjudications; however, have shown little to no improvement.

The Monitor’s Office’s deep concern over extensive delays in SARP case adjudication continues undiminished, despite having been pointed out repeatedly. Not only has there been absolutely no remedial response as of this CMR, the Monitor’s Office learned that shortly after publication of CMR-7, which like CMR-6 also pointed out the acute lack of competent legal staff at Office of the Legal Advisor (OAL) and its negative impact on adjudication timelines, yet another staff attorney was transferred out of OAL to DPS with no replacement. 2

The Monitor’s Office finds that most internal investigations were conducted well and were eventually adjudicated in accordance with facts uncovered by the investigator. There remains considerable room for improvement to achieve a greater level of compliance. SARP continues to struggle with adequate investigations of anonymous complaints, most particularly those that are clearly internally generated or “whistleblower” complaints. To assess this problematic category of complaints, the Monitor’s Office selected a purposive sample of 15 recently concluded anonymous complainant investigations to conduct an analysis. Out of the 15, the Monitor’s Office found that 6 were not compliant, mostly because the accused officer(s) were never interviewed by the investigator, which should be done in all cases where the accusation, albeit anonymous, establishes a potential violation of a very serious nature, which on its face cannot be completely ruled out by independent, established facts. 3

There is yet another glaring and persistent concern over administrative investigation practices where serious wrongdoing has been alleged against PRPB employees by known complainants. When sworn police witnesses provide diametrically opposed versions of material fact(s) in a case involving serious police misconduct - especially cases of alleged corruption, collusion, or reprisal, such a case should not be closed without interviewing all witnesses, including the accused officer(s). In these cases, irreconcilable differences between sworn officers concerning material facts call for exhaustive attempts, including polygraph examination(s) on the part of the investigator, to attempt to resolve opposing versions of fact. Moving forward, the Monitor’s Office has grave doubts about whether PRPB will ever reach substantial compliance so long as this practice persists. Any PRPB employee, irrespective of rank, who is found, based upon a preponderance of the evidence, to have been untruthful during any SARP investigation must be held accountable, irrespective of whether that employee was originally cited as a complainant, witness, or the accused party. 4

Some progress has been noted in documenting SARP case milestones, assignment dates, conclusion dates, supervisory review dates, and area command review dates. This progress should be rapidly improved by creating the ability to include digital signatures within the SARP casefile database, like many major mainland police agencies. The Monitor’s Office continues to find a substantial number of cases where SARP commander’s approval of the case findings is either absent or left undated. Digital signatures could be used to approve 30-day extensions in administrative investigations at the SARP supervisory or area command level, which should eliminate frequent delays for approval (between 3 to 10 days) while the paper copy of the request circulates to SARP Central Command. Adoption of a commander’s digital signature with a time stamp may help reduce or even eliminate this problem.

The Monitor’s Office questions PRPB’s use of PPR 441 to give actual notice (in-hand) as opposed to using other alternate means of notification of a member’s final case outcome or when a disciplinary action is upheld. The Monitor’s Office has observed that this policy frequently leads to months, and at times, well over a year of unnecessary delay by mandating that a PRPB superior officer physically hand a copy of the PPR 441 containing the officer(s) case findings (sustained/not sustained/exonerated or unfounded). The Monitor’s Office strongly recommends the use of alternate means of notification which may include physical delivery to the last and usual address, delivery through PRPB email, delivery by the U.S. Mail (either certified or ordinary correspondence), or to the officer’s registered residence.

Training continues to be an area of poor performance for the entire organization in general, especially in SARP. That said, the Monitor’s Office is very impressed by SARP’s earnest partnership with SAEA and its recent gains in restructuring formative training (SAEA Course REA 114 – SARP Investigations) for its new investigators, including addressing many recently adopted changes in its methodology, rules, and procedures. Although the capacity building phase of the Agreement has long since passed, the Monitor’s Office’s expertise and substantial experience in this area was requested by this partnership during a meeting at the Academy, in which the Monitor’s Office participated. The Monitor’s Office looks forward to seeing the results in the form of a modified formative curriculum for SARP investigators. Formative training aside, PRPB has not yet addressed the dearth of annual in-service training for current SARP investigators. As pointed out repeatedly in the past, SARP has not seen a yearly in-service training component as mandated by the Agreement since the monitoring phase of the Agreement commenced. The Monitor’s Office takes this opportunity to urge the SARP/SAEA partnership to begin working on the annual re-trainer concurrently with the revamp of REA 114 (SARP Investigations), as both should contain similar content and pedagogy.

In the future, it is foreseeable that SARP annual re-trainers could take advantage of synchronous eLearning technology to both deliver content and promote helpful exchange of best practices among SARP practitioners. However, due to the ongoing and extensive changes in its methodology, rules, and investigative procedures, the Monitor’s Office has serious reservations concerning the use of eLearning to effectively educate its current workforce in the voluminous number of official changes to their daily practice. To cite one example, the Monitor’s Office’s recommendations concerning practical interviewing techniques, which have been well-received by SARP, do not in any way lend themselves to a remote learning format. Therefore, at least over the short term, the Monitor’s Office concludes that the annual re-trainer mandated by the Agreement be presential and include practical components. Once this year’s annual re-trainer addresses the numerous changes in SARP methodology, rules, and procedures, ensuing in-service re-training might then be delivered remotely, if feasible. At a minimum, the Monitor’s Office expects to see a plan to address the current need for SARP in-service training during the CMR-9 reporting period.

Adequacy of resources, both human and tangible, continues to remain a concern. The Monitor’s Office is encouraged by the addition of desperately needed investigators for the FIU, which the Monitor’s Office had found to be acutely problematic in terms of staffing. The lack of human resources across other SARP entities, while less acute than FIU, is still an area of concern. In the Monitor’s Office’s private interviews of over 95% of active SARP investigators, nearly 90% of these investigators expressed concerns over the case workload and the deficiency in human resources needed to effectively manage it. The Monitor’s Office encourages SARP leadership to meet regularly with its field investigators and supervisors in listening sessions, in much the same way as the Monitor’s Office has, to gain insight into their needs for resources, both human and otherwise.

While the Monitor’s Office has seen some incremental developments in the SARP vehicular fleet and the delivery of some requested hardware, the continuing dearth of adequate resources not only affects the quality and timeliness of investigations, but it also has a far greater negative impact on the adjudicative timeline of an internal investigation. As predicted in the previous CMR, the Monitor’s Office has heard from multiple sources that this inability to adjudicate open SARP cases in a timely manner has resulted in recent promotional candidates being passed over for promotion. The Monitor’s Office’s concern does not end here. Not a single Internal Affairs office has been relocated away from police facilities despite the Monitor’s Office’s longstanding finding that this practice must end without unnecessary delay. The Monitor’s Office takes note that SARP has been earnest in their ongoing efforts to identify suitable locations for Internal Affairs Bureau (NAI) delegations in settings not associated in any way with law enforcement. Site identification; however, is only the first step in the process and must be followed up by contracting and procurement. As DSP now has both visibility and ultimate authority over procurement for PRPB in general, the Monitor’s Office will follow procurement closely to ensure that it is timely, unimpeded, and suitable to the task.

Lastly, the Monitor’s Office has taken note of recent and very positive developments concerning the PRPB Employee Assistance Program (PAE). Not only have more PRPB members voluntarily sought out PAE for help, PAE has also worked together with PRPB to proactively address institutional changes that may create uncertainty, doubt, and anxiety among the entire membership. The initiatives also include building awareness of mental wellness, physical wellness, and habits that promote both. As any veteran police official knows, fear of and resistance to change is not uncommon in most enterprises but is especially acute within police and other public safety agencies. PAE has also collaborated to publish several recent publications concerning change management and resulting internal fear of change within PRPB. The Monitor’s Office hails this proactive innovation.

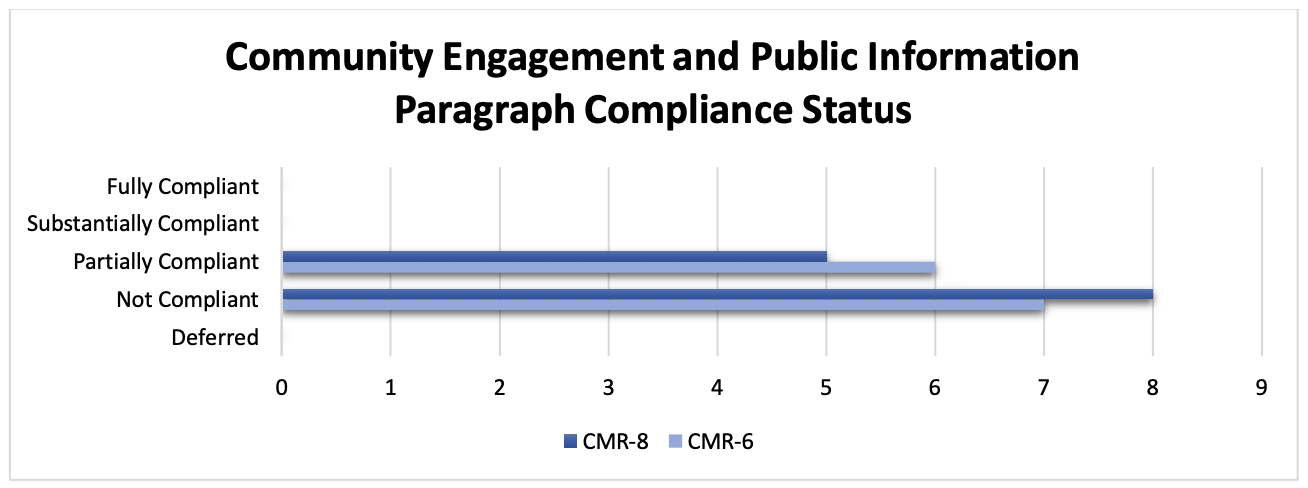

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the thirteen Community Engagement and Public Information paragraphs assessed during this reporting period, reflect similar levels of compliance noted during previous reporting periods. In CMR-6 the last CMR in which all paragraphs were reviewed, 46% of paragraphs (6 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 5 paragraphs were found to be partially compliant while 8 other paragraphs are noted as not compliant. See figure 9.

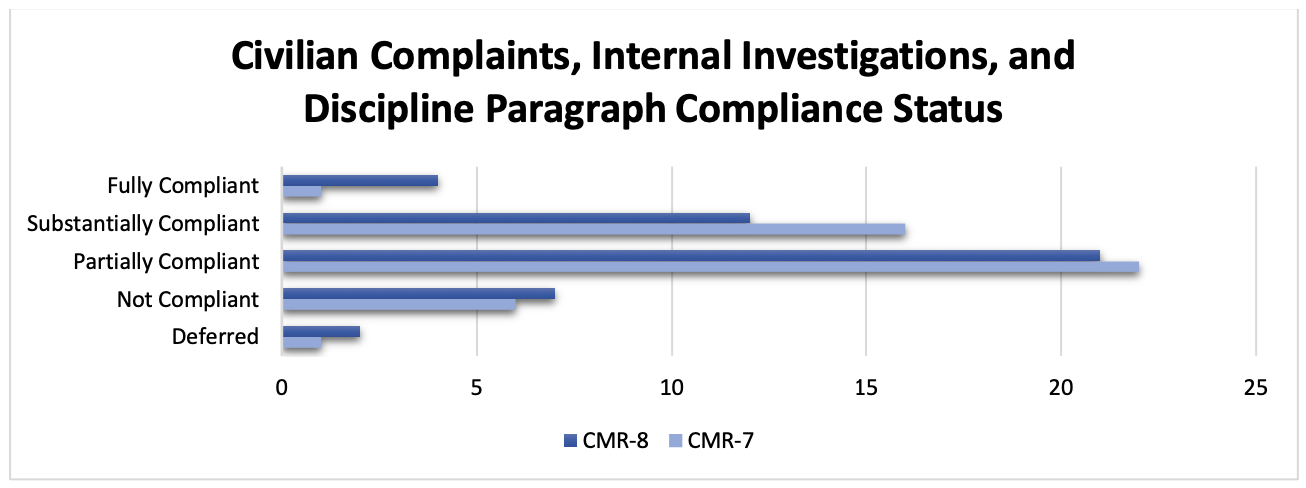

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the 46 paragraphs assessed during this reporting period within Civilian Complaints, Internal Investigations, and Discipline reflect a slight progression in compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-7, 48% of paragraphs (22 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant and 35% (16 paragraphs) were assessed as substantially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 46% of paragraphs (21 paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant and 26% (12 paragraphs) were found to be substantially compliant (3 paragraphs moved to fully compliant. Two paragraphs (4%) were noted as deferred in CMR-8. See figure 8.

8. Community Engagement and Public Information

Community Engagement together with Community Policing and Public Information include 13 paragraphs in the Agreement; 4 of which are assessed annually (Paragraphs 208-210 and 213). A complete review of all 13 paragraphs was captured in CMR-6 and is provided again in this report.

As in previous CMRs, achieving compliance with the Community Engagement and Public Information section of the Agreement has been challenging for PRPB. This has been primarily due to the need of continued competence training and development, which involves problem solving through the implementation of the SARA Model and the development and sustainment of meaningful and goal- oriented interactions with community stakeholders through alliances and outreach. These deficits are notably highlighted by inconsistent supervision resulting from staffing challenges, primarily for agents and first line supervisors, insufficient and varying community policing approaches, straggled efforts to develop a comprehensive performance evaluation system, and the need to efficiently document strategic planning and follow through in community engagement. These, coupled with deficient communication to the public and failure to develop and institutionalize adequate information technology systems to support public transparency around crime statistics, gender violence, UOF, and effective program audits, have set PRPB behind all efforts to achieve substantial compliance during this reporting period.

During this reporting period, the Monitor’s Office met and interviewed various members of PRPB directly involved in community engagement, community policing, and outreach at the district, precinct, and area command levels in 8 police areas, 3 specialized units, the Director of Recruitment, and members of the Community Interaction Committee (CIC), who represent the community within the 13 police areas. Additionally, the Monitor’s Office attended and observed a Conversatorio, a community meeting hosted by the Guayama CIC, two CIC Central spokespersons’ meetings, and a training session on Community Policing for the newly promoted sergeants held at the Academy.

The Monitor’s Office also reviewed related policies and manuals including GO 125 (Press Office Structure), GO 127 (Multimedia), GO 704 (Monthly Meetings) including its corresponding PPRs (704.1 and 704.2), GO 144 (Athletic League), and the Protocol to Report Incidents with Transgender Individuals.

During the second quarter of CMR-7, on July 1, 2022, PRPB launched its community policing module: Sistema de Policia Comunitaria (Community Policing System). These modules were developed by PRPB to record and evaluate direct initiatives and programming by capturing formal alliances, outreach, quality of life issues, informal alliance reports, and problem-solving under the SARA Model. Through this system PRPB intends to comply with paragraph 208 of the Agreement, wherein community partnership development and sustainability, outreach, and problem-solving effectiveness can be measured. The Reform Office introduced agent facilitators and some first-line supervisors to the system by demonstrating the uploading and coding of initiatives. However, no formal training has been given through SAEA in support of the institutionalization of community policing.

The Monitor’s Office received a briefing on the module from the Reform Office during the October 2022 site visit, and a system demonstration during the December 2022 site visit. A review of the system indicates that it is operationally flawed. There is a need for established data quality protocols and guidelines, along with mechanisms to determine accuracy and effective measuring standards. PRPB must be responsible for conducting its own audits to ascertain the reliability of its data for legitimacy, quality, and soundness.

The three-cycle technical community policing assistance program through the Reform Office including field implementation of the SARA Model and the integration between PRPB, the CICs, and the Community Safety Councils (CSCs) for collaboration came to a halt through most of this reporting period to accommodate training the instructors at SAEA and to facilitate training for the newly appointed supervisors in January 2023. As a result, it remains unclear to the Monitor’s Office how this training, while reflective of best practices in community policing, relates to the Academy’s efforts to conduct training on community policing Bureau-wide. Moreover, it also remains unclear to the Monitor’s Office how many of PRPB’s personnel have received training from the Reform Office.

The Monitor’s Office received no evidence in support of training through SAEA in line with policy nor did PRPB provide supporting evidence to prove meeting the 95% threshold of trained personnel during this reporting period.

Community participation through its CICs continues to fluctuate per police area. The CICs are instrumental in providing recommendations to PRPB on policies, recruitment, and implemented strategies based on the experiences and needs of their communities. However, confirming new members remains a longstanding issue directly attributed to the lack of prepared multi-themed workshops, which is a requirement. The lack of required workshops hinders PRPB’s ability to perform its duties and is a contributing factor to the most recent turnover and participation withdrawal. The success of any law enforcement agency is dependent upon its policy and training. Police agencies must have the ability to provide services to the community in a safe and reasonable manner.

Improvement in PRPB’s dissemination of public information is notable during this reporting period. However, PRPB has primarily focused on police activities and criminal interventions due to recent crime waves across the island. PRPB has demonstrated increased use of social and mass media in efforts to solve crime more frequently, proving good results. In addition to these efforts, public meetings are needed to strengthen awareness, educate, coordinate referral services, and to inform the public of the Reform’s progress.

PRPB has not been as effective at using multimedia and internal resources to educate and bring public awareness to community policing, organizational transformation through community participation, crime trends, gender violence, UOF, and non-discriminatory practices among other topics to improve the community’s quality of life. PRPB struggles to report crime statistics, hate crimes, monthly statistics for domestic and gender-based violence, sexual offenses, and child abuse in an adequate, accurate, and efficient manner.

PRPB must proactively work to define and employ consistent and reliable procedures, training, and accountability measures. The targets assessed in this reporting period continue to be unmet and are fundamental to demonstrating progress in community policing implementation, practices, and institutionalization.

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the thirteen Community Engagement and Public Information paragraphs assessed during this reporting period, reflect similar levels of compliance noted during previous reporting periods. In CMR-6 the last CMR in which all paragraphs were reviewed, 46% of paragraphs (6 paragraphs) were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 38% (5 paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant while 8 other paragraphs are noted as not compliant. See figure 9.

9. Information Systems and Technology

Technology revision and adaptation remains slow. During the reporting period data accuracy issues persisted in GTE further complicating UOF data currency and accuracy by supervisory review latency.

Procedurally, IT change management continues to be insufficient, an example of which, acknowledged by the Bureau of Technology (BT), are the needed changes and revisions for PTMS. Overall PRPB’s technology management acumen lacks rigor presumably due to the lack of experienced staff and practice. This is a key concern given the scale of the submitted Corrective Action Plan (CAP) goals and tasks. As important, current governance practices do not exist institutionally to affect optimal outcomes nor de-conflict priorities and issues between stakeholders. For example, requirements management processes lack formality for reconciling and documenting needed changes in GTE, PTMS, EIS, and other systems.

Regarding contracted subject matter experts, AHDatalytics, the Commonwealth’s contractor, continues to contribute to situational awareness by working through critically needed data analysis and its portability to dashboards. The Gartner Inc. deliverables have validated prior observations by the Monitor’s Office and their collaboration with the Parties contributed to the draft CAP. Neither of these activities could have been provided solely by the Commonwealth. Unfortunately, and ancillary to these efforts, although contributions were made by AHDatalytics and Gartner Inc., PRPB’s lack of technology progress during the reporting period may be attributed to their pausing of IT efforts and actions pending completion of the Gartner Inc. IT Needs Assessment and CAP. Thus, given the continuing deficits they have in technology implementation, the Commonwealth’s efforts to improve during the reporting period were again insufficient.

Notable, PRPB’s cyber security stance was not evaluated during the reporting period. For that reason, with the baselining that will occur in the CAP, the Commonwealth, USDOJ, and the Monitor’s Office should assess for cyber hardening and risk mitigation.

Positively, two applications (Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Modules) moved forward and have been acknowledged as substantially compliant by the Monitor’s Office. EIS, however, continues to languish in development. BT eventually received a requirements statement from the Academy and has committed to revising PTMS before the end of 2023. Yet, while positive, the Monitor’s Office was not provided with a discreet schedule for PTMS revision nor the functionality to be delivered. The continuing lack of transparency and poor traceability of documented requirements does not support a premise that management capacity or governance has changed for the positive.

Finally, during the reporting period Body-Worn Camera (BWC) operations were briefed showing promise but the Commonwealth must do better. As briefed, there is not a GO and for that reason PRPB is not fully proofing the technology and concept of operations. The two need not be serial. If the GO is delayed, the Commonwealth should consider splitting administrative tasks so as not to hinder the technical adaptation or experience gained while BWCs are being piloted. Although the CIO noted he could not resolve supervisory failure to follow through on GTE review, no solutions were offered nor “murphy- proofing” notifications that could be automated. As recently as November 2022 the Monitor’s Office was told by agents that they had “no faith” in GTE due to data latency.

Results from the June 2022 Community Survey published during the reporting period show:

- Overall 75% of respondents do not feel that PRPB has the needed technology.

- 70% of community respondents say that PRPB does not adequately publish statistics.

- Only 54% think training frequency is adequate.

- Only 54% think training is sufficient for proper use of IT.

- 60% of agents say that PRPB does not have an adequate early warning system.

Looking forward much remains to be done. This includes:

- Data purification to sustain any level of compliance and data accuracy.

- Implementation of the CAP.

- AH Datalytics contributions are valid and informative and must continue.

- Leverage crime mapping.

- Adequate training by SAEA.

- A cyber assessment should be conducted.

For the above reasons, the Commonwealth’s ability to maintain a self-sustaining technology transformation remains in question and is unachievable without contracted experts.

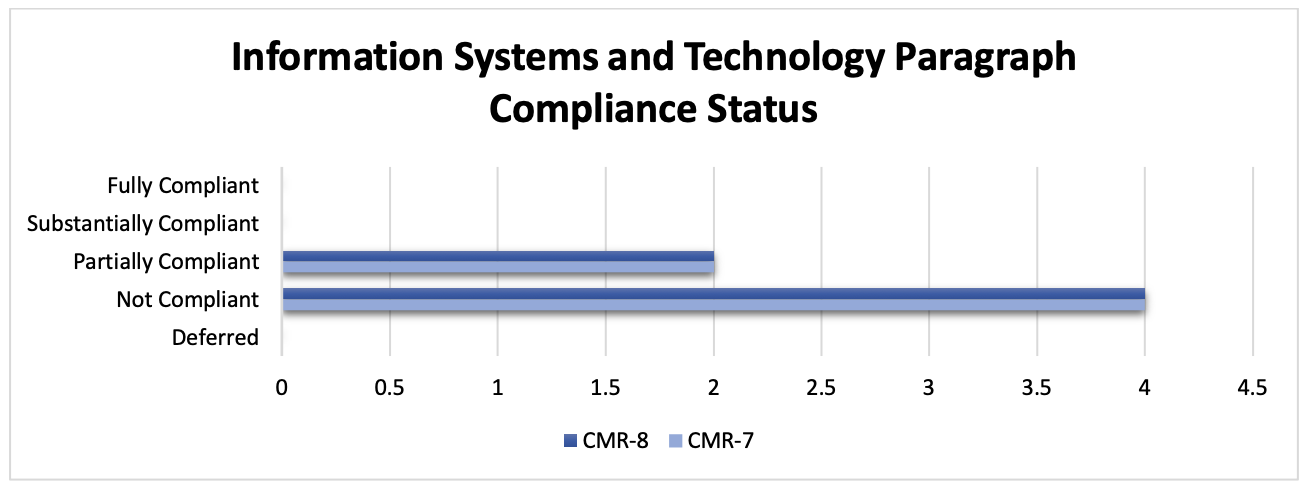

Overall, the Commonwealth’s compliance with the six Information Systems and Technology paragraphs is unchanged from CMR-7 where 33% of paragraphs (two paragraphs) were found to be partially compliant and 66% of paragraphs (four paragraphs) were found to be not compliant. This holds true for the CMR-7 reporting period. See figure 10.

The online version of this

Executive Summary for the

Report is provided for convenience only.

The document filed in The United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico is the definitive version:

Case 3:12-cv-02039-FAB Document 2430-2 Filed 06/13/23