December 2021 Executive Summary for the 5th Report of the Federal Monitor, Covering the Period from April 2021 through September 2021

Federal Monitor

Case 3:12-cv-02039-FAB Document 1918-2 Filed 12/20/21

This is the fifth Chief Monitor’s Report (CMR-5) outlining the compliance levels of the Puerto Rico Police Bureau (“PRPB”) in relation to the Consent Decree entered between the United States and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. This report provides the fifth assessment following the four-year capacity building period established by the Consent Decree that ran from June 2014 to October 2018 and covers the period from April 2021 through October 2021.

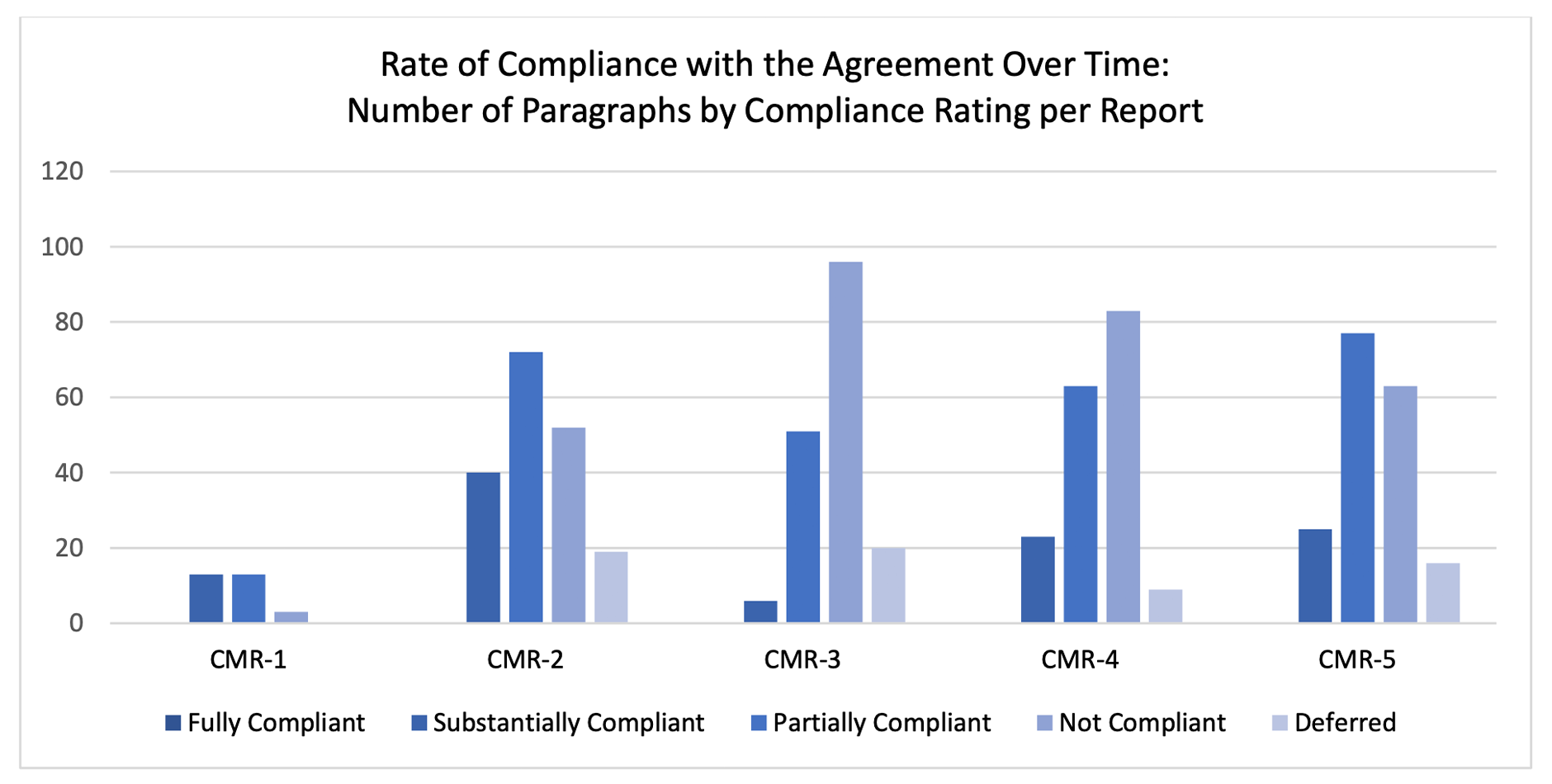

Overall, the compliance assessment in this report demonstrates some progress, particularly in the area of partial compliance. Although PRPB has made significant progress in the development of its policies and procedures, much work remains to be done in the training and practical application of these policies and procedures, see figure 1. Further, when examining the total compliance targets assessed in this report (N=431) in comparison to the previous report, the Monitor notes PRPB has made minor progress during this reporting period, with 42% of compliance targets being met during this reporting period, in comparison to 36% percent met in CMR-4 and 32% met during CMR-3.

The Monitor found that additional work is needed to implement the requirements covering Professionalization, Community Engagement, Supervision and Management, Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination, and Search and Seizures. Issues with the integrity of the Virtual Training System and COVID-19 restrictions have hampered PRPB’s ability to train its members on many topics required by the Agreement. Further exacerbating this issue is the shortage of personnel, particularly supervisors, and the ripple effect that these personnel shortages are having on supervision, performance evaluations, parallel administrative and criminal investigations of police misconduct, and timely investigations of uses of force (UOFs). As noted in previous reports, PRPB’s lack of procedural compliance with Information Systems and Technology and issues with its capacity to identify, collect, disseminate, and analyze valid data on its performance continues to be an area affecting the Bureau’s compliance with much of the Agreement.

Much of the progress made in CMR-5 is attributed to PRPB’s strides in the development of its Virtual Library, development and revisions to its promotional policies, commitment to expand Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) to all areas, development of training on community policing philosophy, and creating a new process to capture UOFs. Because much of this work began in the latter half of CMR-5, the Monitor expects PRPB’s continued efforts in these areas in the next assessment period.

Despite the challenges noted above, the Monitor is encouraged with the increase in collaboration and efforts on the part of PRPB to be responsive to data and information requests. This collaboration is key to PRPB’s full compliance with the Agreement and, ultimately, its sustainable reform.

The following summary provides an overview of the Monitor’s compliance assessment for each area of the Agreement.

1. Professionalization

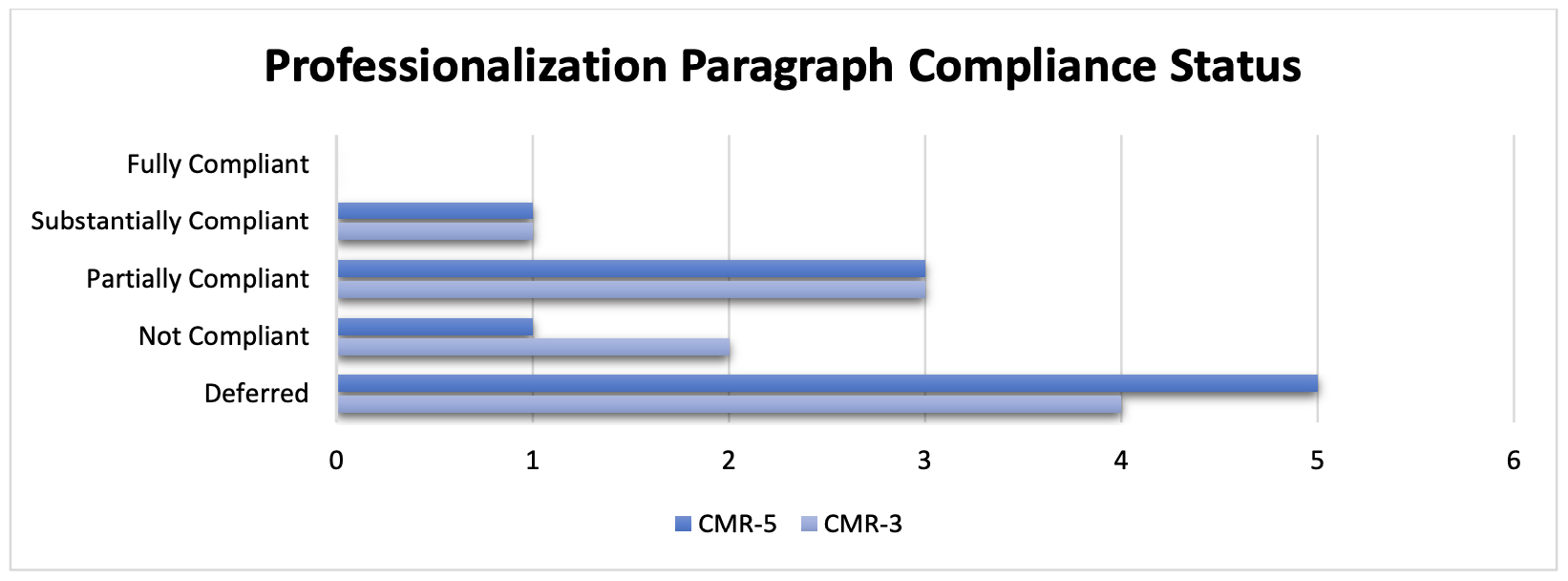

With respect to Professionalization, the Monitor concludes that the PRPB has made additional progress towards compliance since CMR-3, the last report that addressed this reform area. The development of policies for promotions and integrity units, and PRPB’s continued efforts related to ethics and conduct rules are some of the advancements noted in this section. While PRPB has implemented many stipulations of the Agreement in policy and training, the Bureau has not consistently demonstrated the application of these policies and training in practice. It is also important to note that the Office of the Special Master is assisting PRPB with developing the necessary protocols and materials to further assist PRPB’s implementation of this section. The Monitor’s Office looks forward to continued progress.

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 10 Professionalization paragraphs reflect similar levels of progress to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-3 40% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant and substantially compliant, like the current reporting period, where 40% of paragraphs were also found to be partially compliant and substantially compliant. Increases in deferred ratings in the current reporting period are due to no promotions occurring during the reporting period. See figure 2.

2. Use of Force

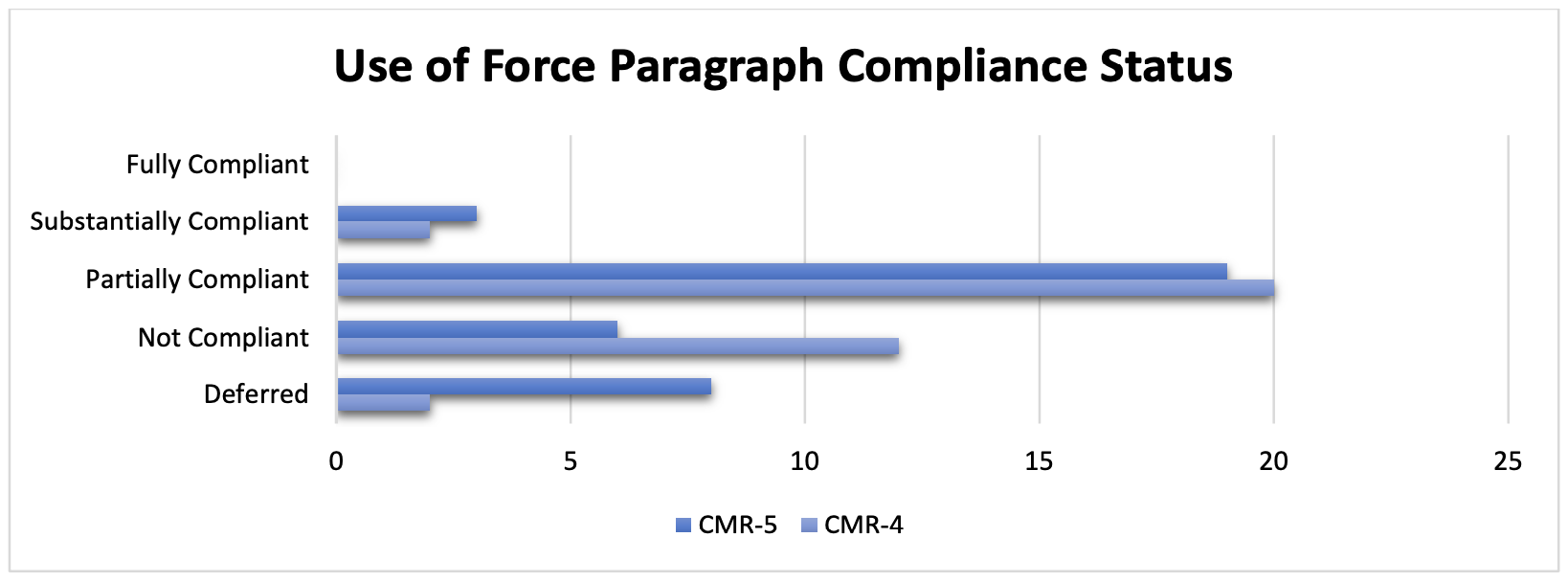

PRPB’s inability to validate its UOF numbers has been a recurring problem that has been identified in the Monitor’s previous reports. For the period covered in CMR-5, PRPB continues to lack a mechanism to validate its reporting of incidents in which force was used, and the number of UOFs in those incidents. However, during the same period, PRPB developed a new process whereby it has replaced all Centro de Mandos PPR-84 on screen forms with PPR-126.2. The Monitor’s Office confirmed via site visits that all 13 Centro de Mandos have completed the transition which took place from June 9, 2021, through August 12, 2021.

The Monitor’s Office considers this a positive first step, which places PRPB on track to develop a valid system to report verifiable UOF numbers. It should be noted that upon his appointment, the Commissioner instructed the Information Technology (IT) Unit of the Bureau to make this modification (replacing PPR-84 with PPR-126.2) as soon as possible. The Monitor applauds the action of the commanding officer of the Reform Unit in accelerating this new process at the recommendation of the Monitor’s Office and the U.S. Department of Justice (USDOJ).

As it relates to FIU, the Monitor’s Office remains concerned regarding the amount of time FIU is taking to complete its investigations. None of the cases reviewed were completed in the time outlined in General Order, Chapter 100, Section 113 (Force Investigation Unit). Some investigations dated back to 2019. In past CMRs, FIU investigations tended to run over the 45-day deadline and, thus, were not closed in sufficient time to provide to the Monitor’s Office for review during the same reporting period that the incident occurred.

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 36 Use of Force paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect similar levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4 56% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 53% of paragraphs were found to be partially compliant. Eight of the thirty-six paragraphs were also noted as deferred in CMR-5, as a result of PRPB’s recent efforts to address the inconsistency in UOF reporting. See figure 3.

3. Searches and Seizures

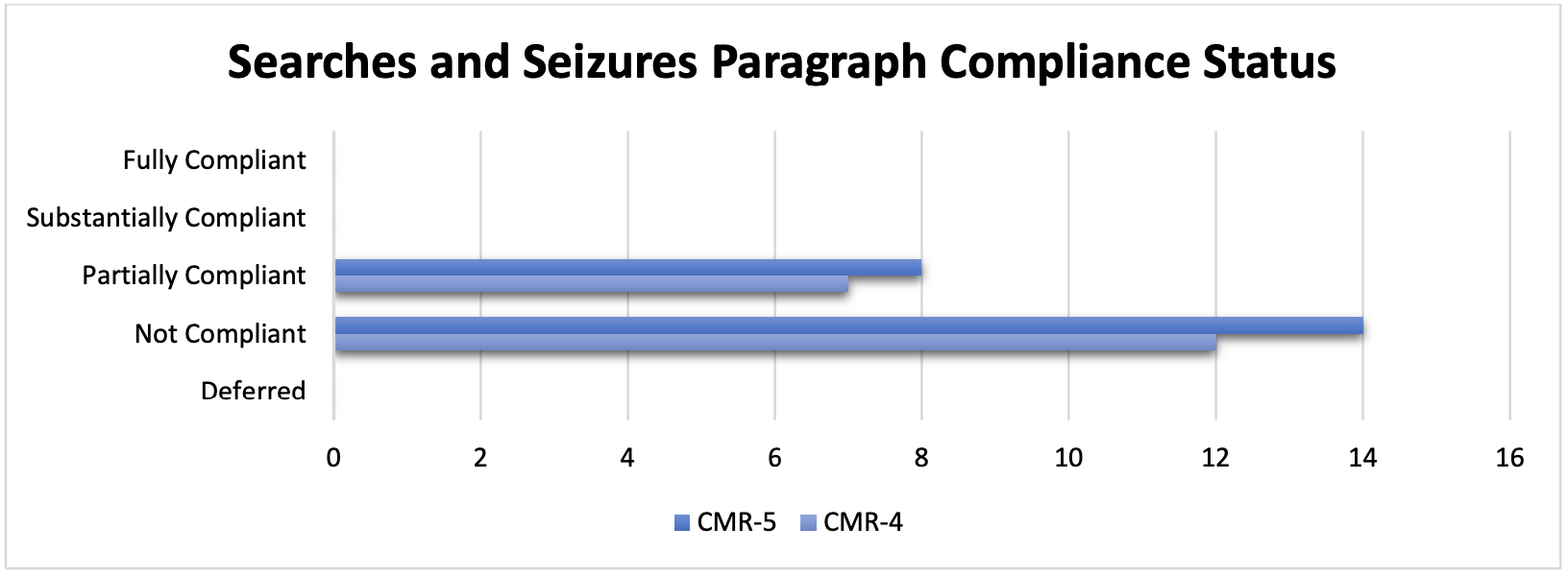

The Monitor’s review of the paragraphs within this section were largely based on the review of the sampled arrest and search warrant files. In his review of 82 arrest files, the Monitor found that most were incomplete, lacking required PPR forms and/or documented probable cause. Of the 64 search warrant files reviewed, under half of the files were missing required forms, such as the police report (PPR-621.1), the Egress/Ingress form (PPR-631.1), and others.

The lack of documentation of probable cause in police reports persists despite the Monitor having alerted PRPB of this problem in past semi-annual reports. In particular, the Monitor found that 100% of the Highway Patrol Division’s reviewed cases lacked documented probable cause for arrest or detention.

Furthermore, during this reporting period, the Monitor’s Office learned through the press that officers from the Highway Patrol Division had arrested five individuals suspected to have entered the United States (Puerto Rico) illegally. The Monitor requested information from PRPB, specifically the arrest report and all other police reports related to this incident. The Monitor’s review of the arrest report and other documentation submitted can be found in Appendix E.

Additionally, in review of the arrest files, the Monitor noted that most copies of the PRPB Miranda Rights form (PPR-615.4) lack a witness signature, although the form requires that officers have a witness sign the form, along with the officer reading the rights to the subject.1 This issue has also been called to the attention of PRPB in the past, but there has been no progress.

Included in the arrest and search and seizure files received by the Monitor were 27 consent searches. In this area, PRPB‘s performance has improved. Of these 27 files, 26 (96%) had consent properly documented on the Consent Search Form (PPR-612.1), with just one lacking a description of the place or item to be searched.

Training on arrests, searches, and seizures has been delayed for over a year, due to a variety of factors that have undermined in-person and virtual training in the PRPB. PRPB’s virtual training system was compromised due to issues with its integrity, and in-person training was very limited due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 22 Searches and Seizures paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect similar levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4 37% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 36% of paragraphs assessed were found to be partially compliant. See figure 4.

4. Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination

The Equal Protection and Non-Discrimination section captures an array of cases including cases related to sexual assault, domestic violence, and related cases that entail any abusive behavior by one person to maintain power over another in a close relationship. It is important that PRPB continue to develop its reporting processes to ensure that PRPB demonstrates its ability to respond to these types of cases in the most effective and professional manner. In this reporting period, PRPB submitted documents that predominately demonstrated either partial or non-compliance with the equal protection and non- discrimination provisions of the Agreement. This assessment is supported by the finding of incomplete documentation within the case files examined, lack of NIBRS implementation Bureau-wide, the need for additional training for investigators, PRPB’s continued efforts related to the 24-hour hotline for the Sex Crimes Investigation Unit and tracking of dispositions of sexual assault investigations.

PRPB has a role in prioritizing addressing sexual assault and domestic violence incidents. In response to these incidents, PRPB can provide up-to-date information and support advocacy programs, which delivers a vital message to any person who is experiencing violence. PRPB is establishing incremental steps in the response process of this section and building upon the policies it has established on equal protection and non-discrimination, but much work remains to achieve compliance.

In CMR-5 29% of the 21 paragraphs assessed are partially compliant. CMR-5 represents the first time this section was assessed for compliance in a comprehensive manner. In CMRs 3 and 4 only 13 and 9, paragraphs were assessed, respectively. As such, it is difficult to compare progress in compliance across CMRs for this given section in CMR-5.

5. Policies and Procedures

PRPB has made demonstrable progress in the development of its policies. Nevertheless, work remains to be done in terms of ensuring that both officers and the public have access to updated policies, and that officers are regularly trained on updated policies. PRPB’s implementation of a Virtual Policy Library represents a considerable step in the right direction. However, the library is still in the initial stages of its release to the public. Further, PRPB will need to incorporate additional measures to ensure that the system is capturing data that may demonstrate whether officers have opened and read new and/or revised policies. Finally, issues with the system’s integrity undermined PRPB’s efforts to deliver virtual training in response to COVID-19 protocols that have limited PRPB’s ability to conduct in-person trainings. As of this report, PRPB has begun initial steps to reinstate virtual training and, as COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, expand in-person trainings. The Monitor will continue to assess PRPB’s compliance with this section and report on further progress in CMR-7.

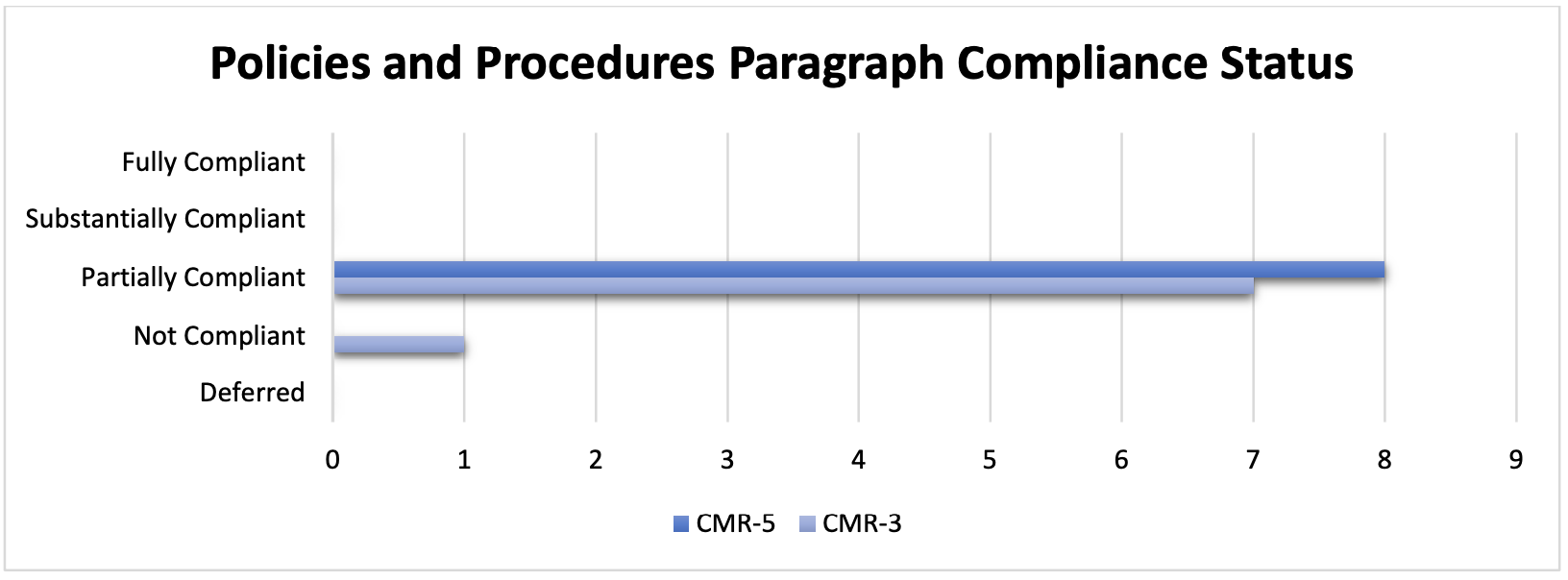

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the eight Policies and Procedures paragraphs reflect continued progress to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-3 88% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 100% of paragraphs were found to be partially compliant. See figure 5.

6. Supervision and Management

Supervisors are essential for bringing PRPB practice in alignment with generally accepted police practices. They serve as the two-way conduit of information between PRPB leadership and the rank and file. It is essential for supervisors to spend time in the field with their agents to evaluate their performance, provide guidance, and hold their officers accountable when not following policies or training. Although some PRPB agents report that their supervisors support them in the field, PRPB compliance with various aspects of the paragraphs within this section require continued efforts. For example, supervisors are hampered in their ability to manage their agents because of the agency’s limited and misuse of its current Early Identification System (EIS) and the shortage of supervisors. For PRPB to achieve compliance with the supervision and management paragraphs in the Agreement, all supervisors must understand and apply management principles in accordance with PRPB's policies, procedures, administrative processes, management systems, generally accepted policing practices, and the Agreement.

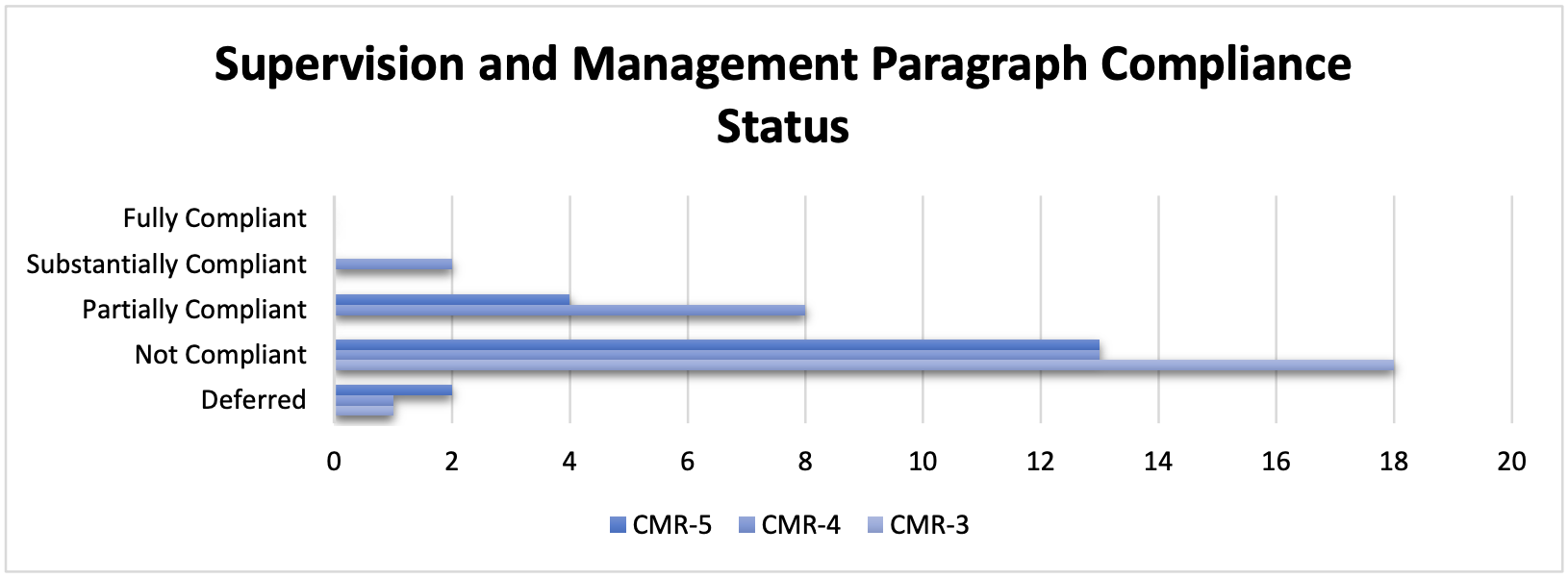

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 19 Supervision and Management paragraphs assessed during this reporting period (5 paragraphs are assessed annually and will be reviewed in CMR-6) reflect similar levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4, 26% of the 24 paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 32% of the 19 paragraphs were found to be partially compliant. See figure 6.

7. Civilian Complaints, Internal Investigations, and Discipline

During this period, the Monitor asked for a list of all SARP investigations closed during the reporting period, irrespective of when these cases were opened. This gave the Monitor a wider cross-section of criminal and administrative cases from which to base his findings upon. Although some of these cases were up to two years old, the Monitor had a chance to observe the inner workings of case investigations from their inception and investigation, through SARP command, review by the Office of the Legal Advisor (OAL), and the optional appeals process or vista informal. The results were comprehensive and revealing.

PRPB continues to make strides towards substantial compliance with the Agreement in the realm of civilian complaints, internal investigations, and internal discipline. While the mechanism for self-policing is apparently accepted by the island’s society and has been proven to work, PRPB must continue to leverage this system. For example, more thorough investigations of anonymous internal complaints can help correct situations of misconduct or perceived corruption, both of which inevitably cause a deleterious effect on morale and esprit de corps.

Proactive use of the EIS should be used to intervene with problematic employees in a timely manner to better ensure the quality of their conduct and service to others. An internal auditing team should be tasked to ensure that disciplinary protocols and corresponding workflows are being carried out both centrally as well as remotely across the island. This auditing team should be a key tool to decreasing the number of unsatisfactory internal criminal and or administrative investigations conducted across the island. Finally, the Monitor has made specific recommendations on enhancing the quality of PRPB internal investigations of all types. These suggested adjustments to Rule 9088, regarding internal investigative methodology, will dramatically improve investigator ability to find the truth and document it.

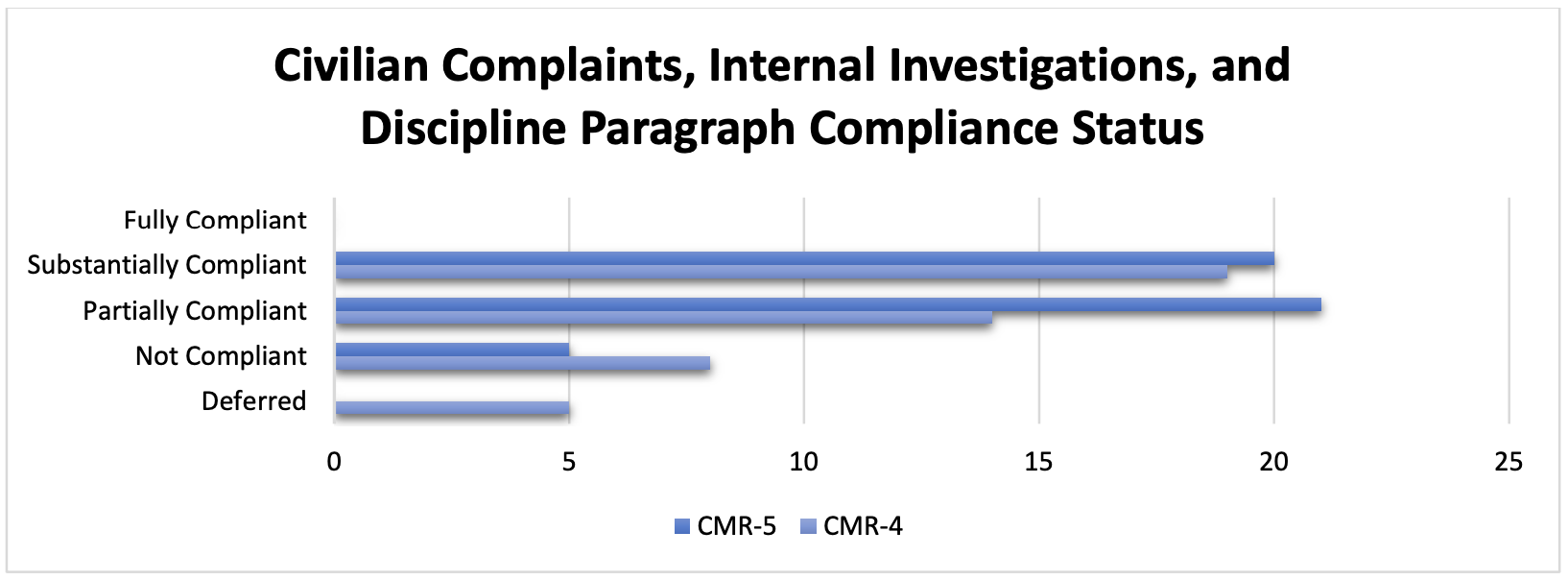

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 46 Civilian Complaints, Internal Investigations, and Discipline paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect improved levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4, 72% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant and substantially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 89% of paragraphs were found to be partially compliant and substantially compliant. Many of these improved ratings were a result of paragraphs being previously noted as Deferred. See figure 7.

8. Community Engagement and Public Information

Community policing is primarily a partnership for problem solving. The community has problems it expects the police to handle, and the police cannot address crime and maintain public order without community support. Public safety and security are a collaborative responsibility of both the police and communities. Community policing includes two core components: partnerships or alliances to create and build relationships between police and communities, and problem solving, which includes the effort to identify and address the primary causes for the commission of certain crimes through community assistance and participation. It is a dynamic process and involves the concerted effort of the police agency to ensure institutional transformation. PRPB has made some efforts to implement community policing, but the geographic deployment of resources directed at community policing have yet to be completed.

PRPB has demonstrated progress in utilizing community-focused problem-solving strategies, including applying the S.A.R.A. model, and developing community partnerships to engage and empower the community, facilitate cooperation, and join in activities toward the resolution of problems. PRPB has undertaken initiatives to solidify these processes, en route to substantial compliance. Recent initiatives include the creation of a directory of Community Safety Councils and an electronic platform to capture and document the development of alliances and problem-solving strategies. These initiatives are still in developmental stages.

PRPB’s strategic plans for recruitment and career advancement must promote the development of a workforce that represents the community and upholds the values of community policing. Furthermore, officer performance assessments must incorporate community policing work assignments, including competencies in problem-solving, implementing the S.A.R.A. model, and any other extraordinary work performed in support of community policing. PRPB has recently embarked in re-training endeavors to strengthen efforts to implement the community policing philosophy throughout its operations. This training is being provided to all area commanders, zone commanders, district directors, and precinct facilitators in each police area, and is expected to be completed by the Summer 2022. The Monitor’s Office will continue to assess PRPB’s progress in its continued implementation of community policing in all the above areas and in training.

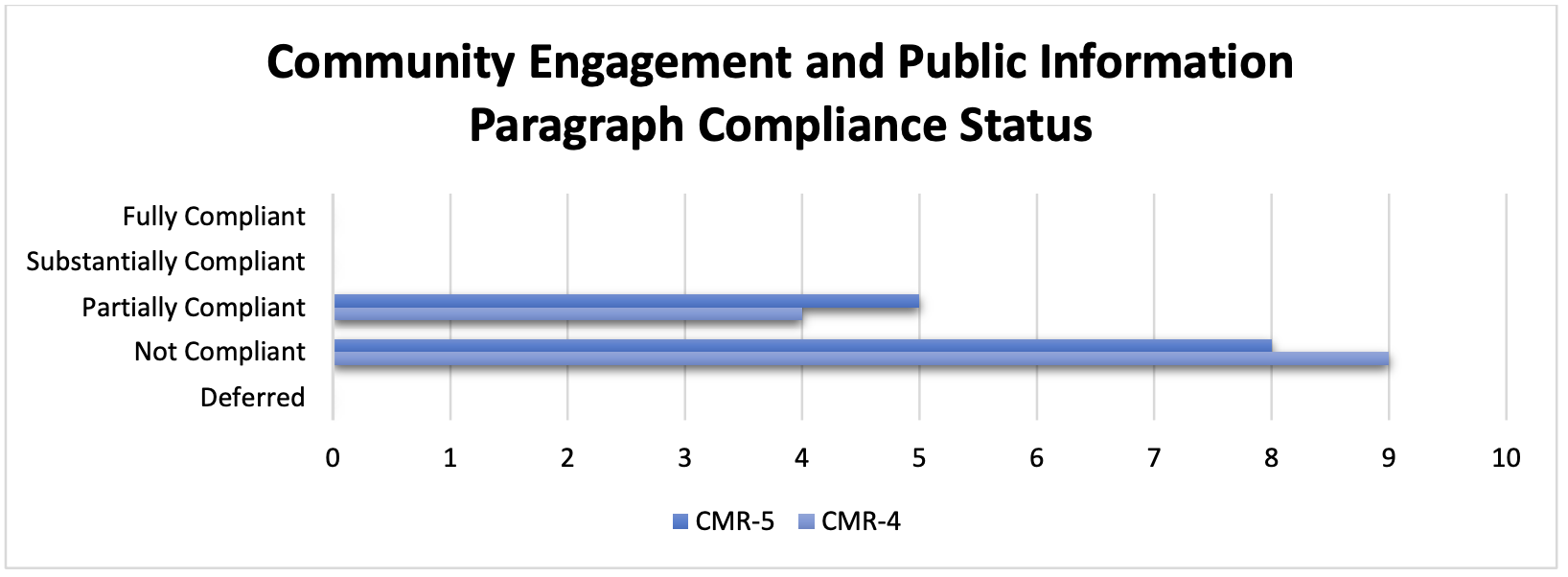

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the 13 Community Engagement and Public Information paragraphs assessed during this reporting period reflect similar levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4, 31% of paragraphs were assessed as partially compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 38% of paragraphs were found to be partially compliant; all other paragraphs are noted as Not Compliant. See figure 8.

9. Information Technology

During the CMR-5 reporting period PRPB continued to make progress toward partial compliance for technology but incrementally and at a slow pace. For example, apart from many of the applications of lesser day to day operational significance (i.e., Project Management and Virtual Library), CAD is still without formal training from SAEA, and EIS, as a conduct intervention system, continues to languish in development and is not implementable. As a reminder, during the CMR-4 development of CAD Form PPR 126.6 continued to iterate and as of this writing has not been operationally finalized.

Positively, the Bureau of Technology (BT) has had some limited progress technologically but as a whole at the agency level, PRPB continues to fall short of procedural implementation that must include not only application and system use in the field but also analytic capacity using data from across the whole of the Department. It is very important to cite that these are not solely BT obligations but rather greater operational policing responsibilities to integrate the technology with operational processes in the field and at headquarters. For these reasons, and while some technology is partially available, continuing adaptations are needed, as is formal training and analytics which are not yet available. Therefore, PRPB cannot be considered to be anything other than partially compliant in many areas for technology and not “substantially” for implementation or analytics as is cited in the methodologies and criteria for monitoring. To achieve a substantial rating PRPB must meet all methodology assessment criteria.

Regarding EIS, its operational status continues to be unvalidated. Throughout multiple reviews and demonstrations numerous issues were uncovered and not mitigated. Further, the Monitors, Special Master, and especially USDOJ expressed significant concern that PRPB’s messaging concerning the use of EIS and its “branding” indicate that EIS may be considered by PRPB rank-and-file to be a punitive tool rather than a diagnostic means to assist and support its agents. This overarching dilemma overshadows the positive partial technology compliance achieved in the Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence modules.

The following observation is unchanged from the CMR-4 period. “As for PRPB’s analytic capabilities, PRPB has yet to demonstrate that it possesses substantive acumen coupled with a mastery of its data resources such that it can measurably exploit its information and data resources to advance the transformation and Decree. This is of continuing concern because while operational staff can query data and generate reports, there is no explicit measurable proof of PRPB using analytic outputs to address the expected transformation within the Decree.”

Finally, the BT continues to lack access to adequate funding and subject matter expert resources. Whether hampered by funding, contracting, or the many other issues the Bureau encounters, PRPB has yet to be able to prove an appreciable level of effective process acumen consistent with technology development and implementation best practices found in the IT industry today. This must change. As an example, repeated requests that operational advocates, sponsors, and process owners attend ongoing demonstrations have gone unmet. Best practices insist that ensuring access to identified authoritative process owners who represent operational use of any application, system, technology tool, or process is essential to effective development and implementation. This experience itself demonstrates that accountability for outcomes is unclear but seemingly left solely on the BT’s shoulders.

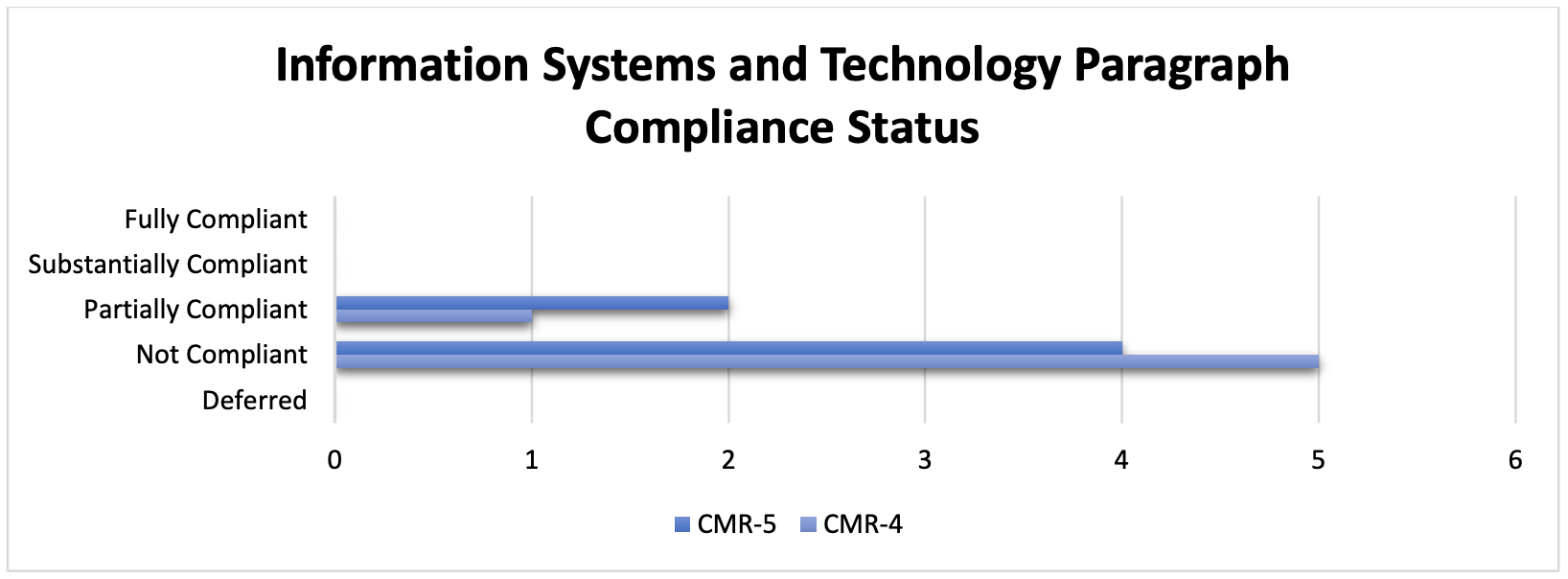

Overall, PRPB’s compliance with the six paragraphs assessed during this reporting period within Information Systems and Technology reflect slightly increased levels of compliance to what was noted in previous reports. In CMR-4, 83% of paragraph were assessed as Not Compliant, in comparison to the current reporting period, where 67% of paragraphs were found to be Not Compliant. See figure 9.

Ultimately, PRPB must be aware that irrespective of progress made so far, if PRPB is unable to sustain advances and transformation, it is possible for PRPB to back slide to non-compliance.

In summary, additional work is needed to develop and/or revise training and in operationally implementing the requirements in many areas of the Agreement. While the Monitor’s Office continues to acknowledge the increased efforts and commitment on the part of PRPB’s Reform Unit to accelerate implementation of many of the recommendations made, much of these efforts hinge on PRPB’s continued work on its information systems and technology, reinstatement of its training, and addressing the implementation issues identified by the Monitor.